Crisis of a generation: Shuttered schools in the Philippines could mean a lifetime of poverty

A pilot run of face-to-face classes is set for next month, but some schools have withdrawn even before it begins. For the Philippines’ poorest children, the losses keep piling up, Insight finds out.

Jonathan Mapa, 12, and his family survived on rice, water and salt every time there was a lockdown.

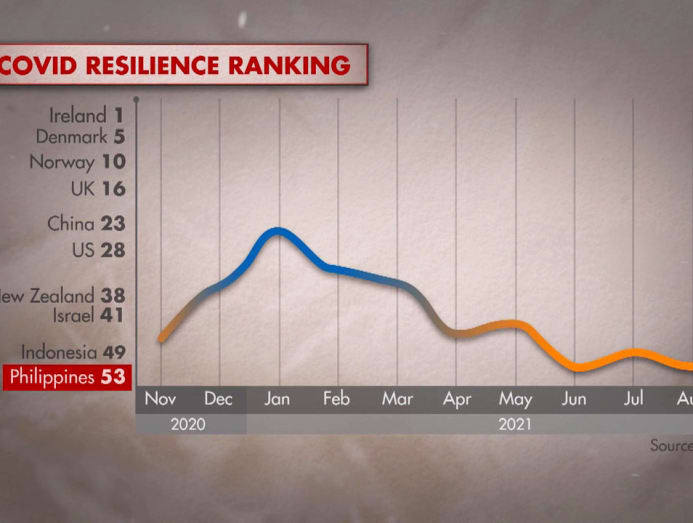

MANILA: The Philippines, one of only two countries in the world that has not resumed face-to-face classes due to COVID-19, is gearing up for a limited re-opening of up to 120 schools next month.

But for 12-year-old Jonathan Mapa and around 2.3 million children said to have dropped out since March last year, it may be too late.

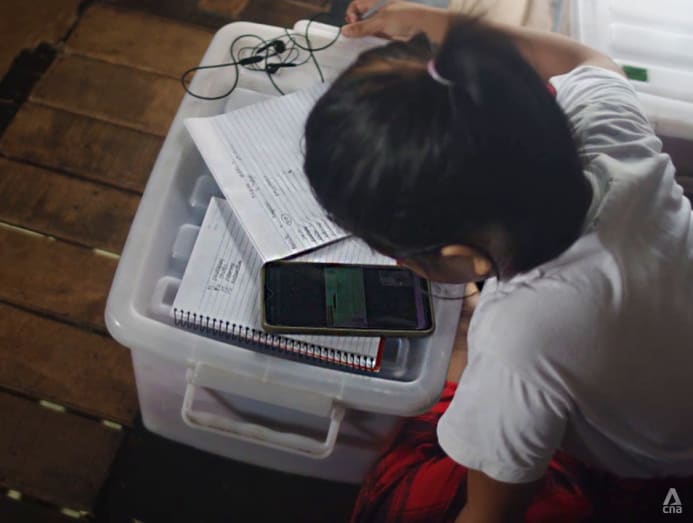

When schools first closed, Jonathan used his sister’s phone to tune in to online classes. But that stopped after she had to relocate to another city for work, and the family could not afford another phone – not when they were surviving on water, rice and salt every time there was a lockdown. “We had no more money to buy more food,” said Jonathan.

“I was envious of the other children. They owned cell phones,” he said, breaking down in tears.

And to the dismay of his father, Jonathan took up hazardous work nine months ago to earn some income for his family.

But even for the luckier children who have been able to continue their education, learning has suffered. Surveys show that remote and modular learning outcomes have been dismal.

The cost of shuttered schools will mean decades of lost and reduced wages for these children as they remain trapped in the cycle of poverty, experts say. New data also shows that the learning crisis could hurt the Philippines’ productivity and economy for the next 40 years.

The current affairs programme Insight speaks to some struggling families and examines the troubling implications for the archipelago of 110 million people.

BASIC NEEDS ARE A STRUGGLE

Before the pandemic, bicycle taxi rider Jonathan Mapa Senior earned enough to buy food, pay the bills and school fees, and give his son an allowance of 10 pesos (US$0.20) a day. Now, he cannot afford the rent or electricity and water.

Although many children in his community in Tondo, Manila began scavenging for recyclable items during the COVID-19 pandemic, the 47-year-old had not wanted his son, also called Jonathan, to take on the dangerous work.

“I only learned about it when I arrived home one day. I asked (my wife) about Jonathan’s whereabouts… he did not ask for permission because he knows I won’t allow it,” Mapa said. “He is too young. He might get into an accident, then he might get caught by the city government.”

Lockdowns caused the streets to be emptied of passengers and the government gave out an average of US$78 a month to families like theirs to compensate, but this was barely half of what Mapa used to earn.

When the government was handing out electronic tablets, Mapa joined the long queue, his wife Normelita told Insight. But supplies ran out before he could secure one for his son.

Jonathan has not given up on school, although he does not know how he will find his way back. He had, in fact, started scavenging to save up so that he could study again. Often riding an old pedicab on an empty stomach, he might earn only US$0.40 from an afternoon’s effort.

Just when he had saved up 1,500 pesos (US$29.50), the family ran into another setback. His mother, who has arthritis, fell ill and the money had to be used for her medical treatment.

Observers say the government has overlooked the pandemic’s impact on the country’s youths, and the closure of schools will hurt an entire generation.

“I don't want to sound overly pessimistic. But I think we have to recognise that we are really facing a crisis that is not only a learning crisis; it's a generational crisis that will affect all segments of the society,” said Dr Edilberto De Jesus, senior research fellow at the Ateneo School of Government.

Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte famously said in May last year that he would not allow students back to school until a vaccine was available. “If no one graduates, then so be it,” he had said.

The Philippines has logged over 2.7 million confirmed cases and over 40,000 deaths from the virus so far. It has vaccinated less than a quarter of its population.

Besides the Philippines, Venezuela is the only other country in the world that has not resumed face-to-face classes.

It's a generational crisis that will affect all segments of the society.

De Jesus warned that if the government doesn’t look after the country’s 26 million or so students, more will drop out and later become “an even bigger drag on the society”.

Closing all schools in the country was not the right approach to take, said Vincent Ramos, a PhD candidate in economic policy at the Hertie School in Berlin, Germany. This is because not all regions and provinces are affected in the same way by COVID-19.

WATCH: Insight: The Hidden Cost Of COVID-19 On Philippines' Youth (48:22)

De Jesus said the country may have to, once again, rely on non-governmental (NGOs) and civil society organisations to supplement the government’s efforts to meet people’s basic needs.

But Elenita Reyes, village chairwoman of Barangay 105 in Manila, said the pandemic and movement restrictions have led to reduced aid from NGOs.

“Before the pandemic, we were doing well. We get help. Children were given shoes, food, all kinds of vitamins by NGOs,” she said. “But now, they can only give us one-fourth or half of what they usually give.”

OVERWHELMED BY REMOTE LEARNING, MENTAL HEALTH SUFFERS

Even for children who have managed to continue their education, remote learning outcomes have been dismal.

Civil society group, the Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education (SEQuRe Education Movement), surveyed almost 6,000 respondents comprising teachers, students and parents between end-June and early July this year.

Seventy-three per cent of 1,299 students surveyed confirmed that they have “been absent (from) online classes or failing to turn in modules on time”. The majority said they learned less than when they were going to school.

“It is apparent that the lack of teaching and learning resources, as well as the ill-designed distance learning programme hindered effective remote learning,” the civil society group concluded.

It hurts to see your grades suffering while your parents are struggling for you.

Judith Damiar, 14, has seen her grades slip during remote learning. As her family lives in Wawa, a barangay in Rizal province with poor or no internet connection, she opted for “modular distance learning” where teachers hand out and collect paper-based modules at least once a week.

But Judith has no one to ask when she doesn’t understand what she is reading. “With modules, the teacher can’t really explain them because they’re not here. The modules also can’t be explained by our parents because they weren’t able to study properly,” she said. Her father, Dionisio Damiar, 56, does odd jobs for a living.

“The words used are kind of deep,” said Judith of the school materials. “Sometimes the questions would run in my brain in circles.”

She added: “It hurts to see your grades suffering while your parents are struggling for you.”

Such feelings can lead to mental health effects including stress, anxiety, depression and panic attacks in children, said Professor Lizamarie Campoamor-Olegario, SEQuRE’s lead researcher.

“The students share these mental concerns were triggered by being overwhelmed with the class and household duties, limited or lack of social interaction and inability to understand the lessons for distance learning. Or they had difficulty in self-directed learning,” she said.

LOSSES OVER THE NEXT 40 YEARS

The authorities have produced data in an attempt to calculate the pandemic’s toll on the economy and its people.

Last month, the Philippines’ National Economic and Development Authority estimated that the loss from reduction in future wages and productivity due to suspension of school, and lost wages of parents who accompanied their children for online classes, would amount to 11 trillion pesos (US$220 billion) over the next 40 years.

Losses from premature deaths, sickness and inability to access treatment for COVID-19-associated illnesses would amount to 4.5 trillion pesos over the next 40 years, it estimated.

Before the pandemic, 19-year-old Juriel Natividad’s family was doing well enough for him to enrol in a private school. He should be a second-year film student in university, but is instead a drop-out. The reason: His mother Alma lost her job as a massage therapist in the United Arab Emirates.

The resident of Antipolo in Rizal province now spends his time tending to the family’s small store, and the income can only cover their daily needs. He wants to look for another role, but says the job market is tough.

Instead of studying, I have become (a) good-for-nothing here at home. I am now a burden to my family.

His mother did not get angry when he dropped out, but Natividad said she is disappointed. “After all her years of sacrifice, after pouring in all her best efforts, in one moment, we ended up this way.”

The young man wishes the government would help children return to school, and give people like him a hand in finding a job. “Our generation is suffering from the worst mental instability, like me. I cannot avoid feeling anxious and depressed about our hardship,” he said.

Philippine news site Rappler reported this month that 59 public schools have passed the assessment by health officials to pilot limited face-to-face classes, but 29 later withdrew. Reasons include the local government units or parents not being in favour of face-to-face classes.

Schools must have the written support of parents and students to take part. Up to 100 public schools and 20 private schools may participate in the pilot, which is scheduled to end on Jan 31 next year.

If the pilot run is found to be safe and effective, the number of schools on board could increase, Education Secretary Leonor Briones said in September.

For De Jesus, the importance of education cannot be over-emphasised. “Unless the kids are educated there is no hope for them to improve their standing in life,” he said.

For the children and their families, the future hangs in the balance.

“If fate is kind, I wish Jonathan would earn a degree in teaching, to be a teacher, or as long as he finishes his education. That’s the only thing I could bequeath him,” said Mapa.

Judith, who wants to be a police officer, put it simply: “I hope I can finish my studies. Then, I hope COVID will finally be eradicated.”

Watch this episode of Insight: Asia's Lost Generation: The Philippines here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.