Pulling together in creative ways, to better feed food insecure Singaporeans

There are over a hundred food assistance groups helping the needy. But why are good intentions sometimes falling short of meeting needs – and can groups overcome their differences to work together?

Madam Loh, 88, with some of the food donations she's accumulated over a couple of months, some of which is not appropriate for her diabetic condition. (Photo: Goh Chiew Tong)

SINGAPORE: At 9am every day, 80-year-old Ho Hon Kee hobbles slowly on arthritic, bowed legs down to his void deck, to collect two styrofoam boxes of cooked food given out by a charity kitchen.

Today’s free meals – one for his lunch, one for dinner – consist of generous servings of rice, stir-fried spinach, a braised soy sauce egg, and fried ikan kuning. It’s more than enough for his modest appetite, but there’s more to come.

Upstairs, on his return, he finds by the door of his one-room flat another still-warm packet of food, this one left by his Meals-on-Wheels provider. There’ll be another meal drop-off from them in the afternoon, bringing the day’s total to four.

Inside the untidy flat, there’s no space at the small dining table for Uncle Ho to sit and eat. That’s because there’s a small mountain of donated biscuits (cream-filled, hi-fibre wheat crackers, oatmeal cookies, even croutons) and two unopened loaves of white bread. Elsewhere, on the floor and other random surfaces, lie months-old unopened snacks and other food packs.

“A lot of food hor?” he remarks sheepishly in Mandarin. “People bring to my doorstep; sometimes they’re from the Residents’ Committee (RC), sometimes the church nearby.”

He’s tried eating some of the cookies and croutons, but they are too dry. And too hard for his dentures and toothless gums.

As for how he gets through four packed meals a day, he doesn’t. He picks out what he likes.

“Slowly eat, cannot finish just throw,” he said, urging us to take one box back to the office with us.

Having too much food sounds like a happy problem for old folks like Uncle Ho, who finds it a struggle to walk to the coffee shop and who doesn’t have the equipment to cook at home.

Surely, it’s better to have too much help, than none at all?

WATCH: Hunger in Singapore – the documentary, part 2 (19:53)

WHEN HELP IS TOO MUCH

But Uncle Ho’s surfeit reveals the complexities involved with Singapore’s “many helping hands”-based landscape of food assistance.

In a 2018 paper on food insecurity, researchers from the Lien Centre for Social Innovation identified a total of 125 food support organisations based on their online presence. They range from non-profit organisations and charities with Institutions of a Public Character (IPC) status, to soup kitchens, Meals-On-Wheels providers, and informal volunteer groups.

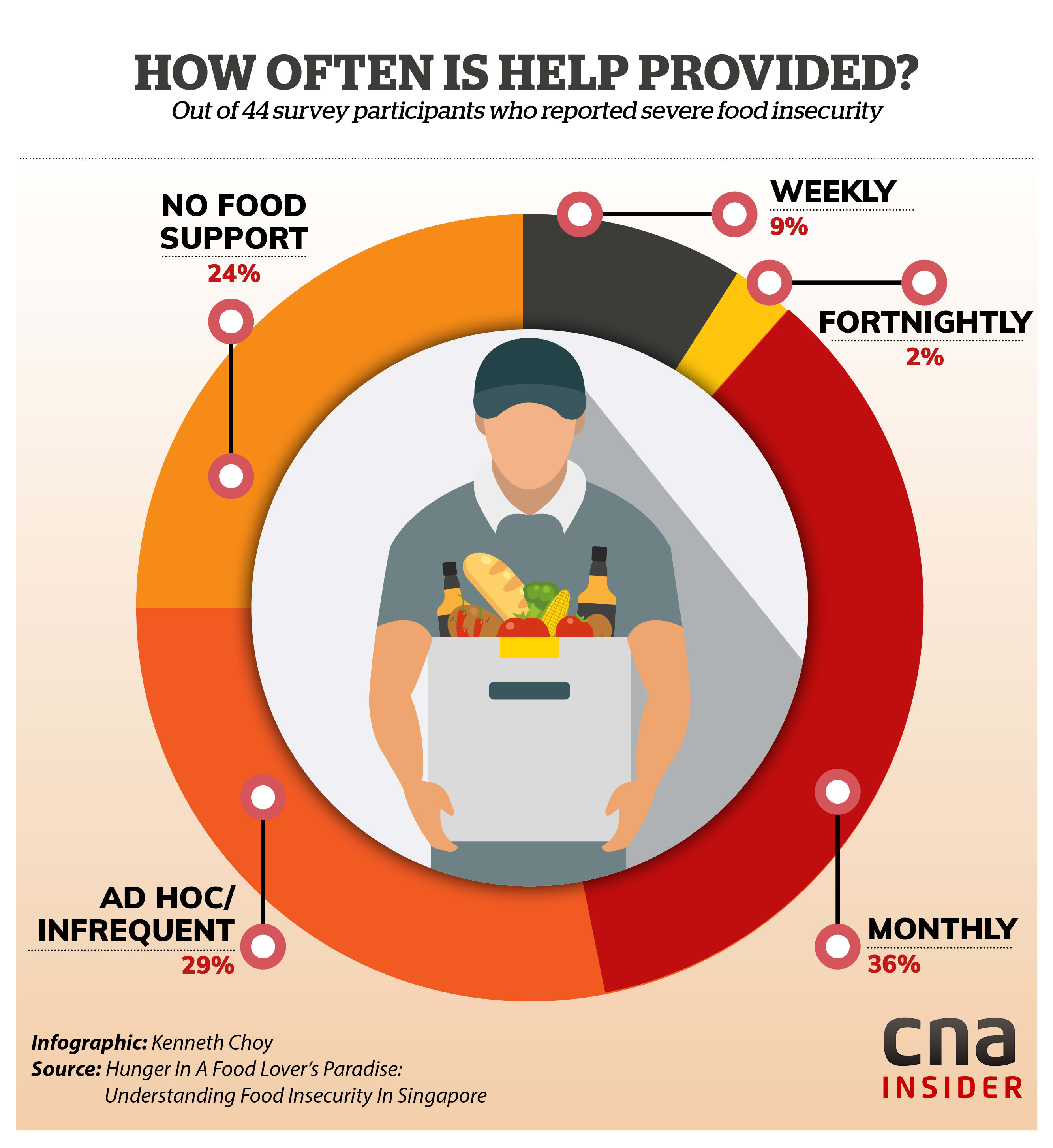

And yet, the study also found that more than half of the 44 severely food-insecure households interviewed had infrequent or no food support at all – which suggests inefficiencies in the charitable food support eco-system.

Charities that CNA Insider spoke to say the duplication of assistance comes down to the lack of coordination or information-sharing among the groups.

Nizar Mohd Shariff, 49, who founded Free Food For All (FFA) six years ago to provide free halal meals for the less fortunate of any race or religion, was “shocked” when he realised that the beneficiaries he was serving were getting help from multiple sources. “Why is there no central database that indicates if this person has already received food from an organisation?” he asked.

At Ang Mo Kio, for instance, “the residents told us that between FFA and whatever they were getting from others, there was just too much for them to consume,” Nizar said. So he has decided to back out of the area and channel much-needed resources elsewhere.

The Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) noted that “generally, areas with a sizeable and older cluster of rental flats tend to be more well known, and thus better served by food support organisations”.

The consequence? “This may lead to wastage in some cases, and some households remain underserved, especially those who do not live in rental flats,” said an MSF spokesperson.

MP for Jalan Besar GRC Denise Phua has tried to “keep a tighter rein” to avoid duplication of services in her ward. But, “it is not always easy because some donors prefer to do what they want, and are not concerned about partnering with others to reach the unreached,” she said.

Food support groups typically give out the same kinds of non-perishables with a long shelf-life. So, overserved beneficiaries end up with too much rice, instant noodles, biscuits, and canned sardines and baked beans.

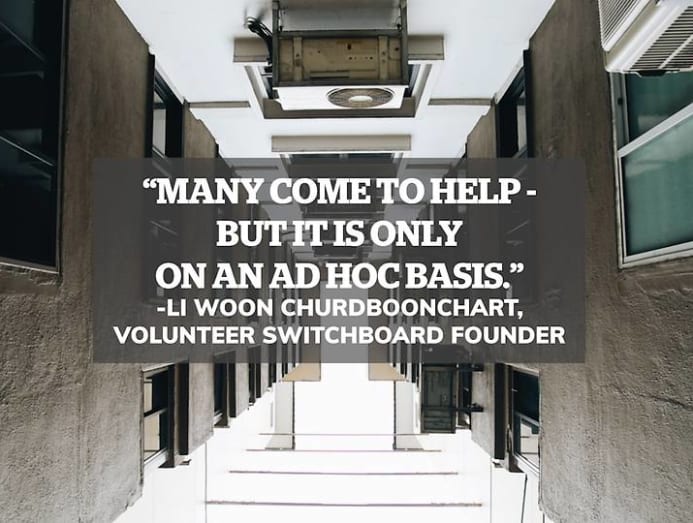

“You can tell when one household is being served by three, four groups,” said Li Woon Churdboonchart, founder of social enterprise Volunteer Switchboard which runs Project Home Sweet Home.

Its volunteers, who deliver food rations every month to the elderly poor at Jalan Kukoh, make it a point to go through the packs with them. “We will take out every single item and ask, would you eat this? If you don’t, we’ll take it back,” she said. The seniors even pass them surfeit items given by other groups.

The frequency at which rations are distributed is a problem.

Every Wednesday Aunty Loh, 88, must pick up two heavy plastic bags of rations that she signed up to receive from a temple.

It’s too much for her, but she claims she has no choice. “If one week you don’t come and pick up, they will strike your name off. They won’t give you the next week,” she said in Mandarin.

When CNA Insider visited her one-room rental flat with volunteer group Keeping Hope Alive (KHA), there were at least 10 bags of rations sitting untouched. Several packets of rice and bee hoon had become infested with bugs, while a tin of something that had leaked was crawling with maggots.

The food-giving usually intensifies around periods like National Day or Chinese New Year, when ad hoc groups show up to help. And so, the elderly residents “accumulate more and more”, said Fion Phua, 50, KHA’s founder.

“They think that so long as something is not opened, it still can be eaten, never mind the expiry date.”

Her volunteers visit a different rental block every Sunday, and help the residents to clean their flats and clear unwanted items. The bulk of Aunty Loh’s food donations had to be thrown away because they had spoiled or long expired.

Sometimes, the 88-year-old said, she passes the food to her neighbour. “Her husband is in jail and she has one child. It’s tough and she has to work.”

THE OTHER EXTREME: LITTLE TO NO AID

Just two floors down from Aunty Loh, an eight-year-old girl was going without lunch, and was drinking water to feel full. It’s a stark representation of how, even in the same block, one can find both the overserved and the underserved.

When CNA Insider first met Katie*, she, her grandaunt and her dad were struggling without regular food assistance, while most of their money went to paying off debts. They had a simple dinner at night. “It’s not like we’re super-hungry,” Katie said.

READ: Why in a cheap food paradise, some Singaporeans are still going hungry

Typically, the food charities work with case referrals by the family service centres (FSCs), RCs, senior activity centres and community centres. But the family didn’t seem to be on any group's radar.

Their plight came to Fion’s attention only because she chanced upon Katie along the corridor. The family has since been getting help from Keeping Hope Alive, including with groceries and regular meals.

Then, there are cases like Serene Loh, who finds the typical bag of rations – while more than enough for an elderly person – to be far too little for her family of six.

“We used to receive food rations from the FSC every two weeks. but we can finish them in a day,” she said. “My kids are still growing so they will eat a lot.”

That could be one reason why a few of those receiving frequent food aid – once a week or fortnight – still reported being severely food insecure, in the Lien study. That is to say, they went without eating for a whole day, or couldn’t afford to eat when hungry.

Serene feels that the seniors living in her rental block get significantly more from the volunteer groups that come by. “It’s not fair that only the elderly get so much help,” she said.

THE HIDDEN PROBLEM

Others fall off the radar by a twist of geographical fate.

Take the Chin Swee area, said KHA’s Fion. “People only see blocks 51 and 52 because these are the rental flats with a majority of old people.

“But just behind Chin Swee is Jalan Minyak, blocks 4, 5 and 6. You don’t see many elderly folks there because there's a mix of families with children as well. So, if you focus only on serving the elderly, you wouldn’t enter that area.”

When CNA Insider spoke to several residents at Jalan Minyak, we were told that a food charity used to serve the area every week until they stopped three months ago, for reasons unknown.

“They would send one or two vans every Tuesday. Sometimes we’d get fresh groceries, sometimes rations,” said a resident in his 40s. “Whoever wanted could just come and take.”

Other groups had also offered food assistance occasionally, but have not been seen lately, said a resident.

Over at Holland Village, behind the bustle of its bars and chic cafes, is a single block of rental flats at Holland Close. “People don’t see it because the focus is always on big estates,” Fion said.

“Plus, this kind of flats are not near the MRT station.” This makes it more inconvenient for volunteers to lug large quantities of rations.

In that block, 500m from folks sipping artisan iced lattes, KHA and CNA Insider found Ahmad, his wife and their five children in a one-room flat. Their youngest child, born four months ago, was fast asleep on a dirty, sunken mattress.

Providing for her diapers and milk powder on Ahmad’s earnings of S$650 as a part-time cleaner means they have that much less for food. They get monthly rations from a charity – but it’s all consumed well before the month is up. So when Fion and her volunteers came by with hot vegetarian porridge donated by a hotel, Ahmad asked for six servings.

Families like his are why the KHA volunteers visit a new area every two to three weeks. “To be honest, if you ask me where you can find people in need, just open up to any location on the Singapore map,” said Fion.

‘GHOSTING’ AID

Despite the sheer number of food support groups on paper, in reality, many of these efforts to help can be irregular.

That’s why Volunteer Switchboard has been focusing on the low-income neighbourhood of Jalan Kukoh for six years, even though, on the surface, it seems like “everybody wants to help there”.

“A lot of people ask me, Jalan Kukoh is overserved, why are you still there?” said Li Woon. In response, she points to how she has seen well-intentioned efforts peter out. “One group was there to give bread, so we didn’t include bread in our ration packs.

"Then suddenly, one day, we realised they were gone.”

Not every group has the ability to function as a full-fledged food charity, noted Nichol Ng, the co-founder of The Food Bank Singapore, which collects excess food from companies or individuals and channels these to the needy through community partners.

“Under the National Council of Social Service umbrella, there are over 2,000 members and many of them have some kind of food programme,” she said. “But not many have a living, breathing food distribution effort that spans 365 days a year.”

Food From The Heart (FFTH) is one of those that do have a sustained programme. The 16-year-old charity is pledged to “alleviating hunger through efficient distribution of food”, in the form of food packs that currently feed 3,600 families – some, who have been beneficiaries for many years.

Said CEO Sim Bee Hia: “It’s a sustained effort, not something where you collect food this month and then the next month you won’t have. That’s the worst thing you can do to them.”

WHEN FOOD BRINGS MORE (HEALTH) PROBLEMS

The frequency and even spread of food assistance aside, another issue is that of quality of donations, and whether these match the beneficiary’s needs – especially when it comes to their health.

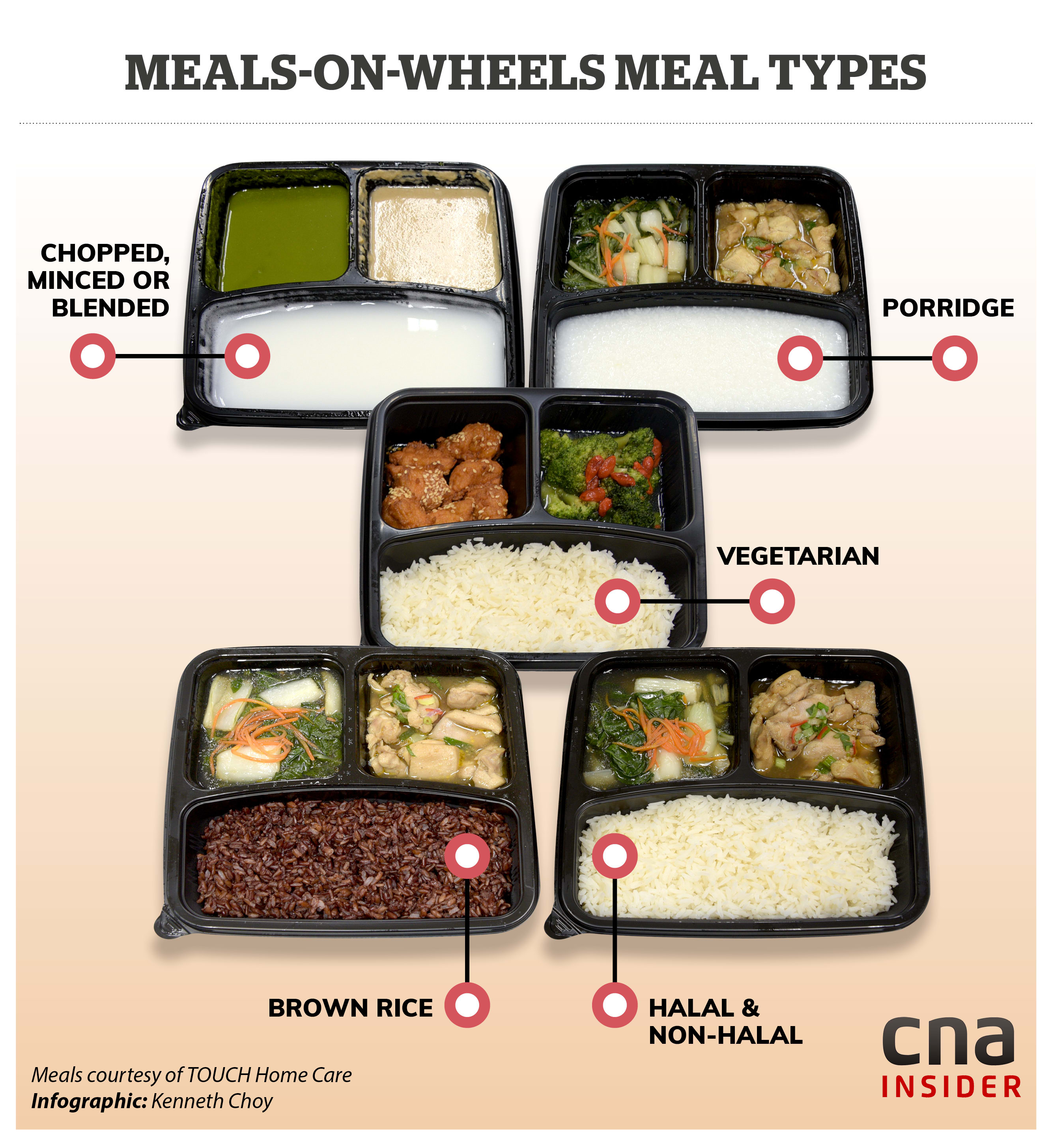

Under the Meals-on-Wheels programme – funded by the Agency for Integrated Care, to provide homebound individuals with meal deliveries at a subsidised rate – service providers must cater, upon request, to clients’ special requirements such as meals for diabetics or soft diets.

But this aside, there is little to dictate what other food assistance groups should give. Take Aunty Loh, the 88-year-old inundated with food donations, who should not be eating some of the rations she is given.

“I have diabetes,” she said as she injected herself with an insulin pen, then threw the used needle into the trash with the syrup-heavy canned longans thst Fion's KHA volunteers had discarded.

Aunty Loh also has high blood pressure and high cholesterol, and takes more than 20 pills a day to keep her ailments under control.

Holding up a can of fried dace fish with black beans, Fion sighed: “This is deep fried, it’s salty, it’s preserved. Aunty already has the three ‘highs’. Let me tell you frankly. If she eats all these, it is a slow suicide.”

In April 2018, the Health Promotion Board (HPB) released guidelines for charities and donors to choose healthier products when providing food for beneficiaries.

But former academic Dr Jenson Goh, who looked at Singapore’s food system as part of a course he once taught at NUS’ Residential College 4, thinks it’s insufficient considering the “complex” nutritional needs of the food insecure. “The guidelines are a broad stroke, but there are very different, unique individual needs. The approach has to be personalised,” he said.

Others note that despite the guidelines, the standard “starter pack” of food rations contains items that don’t actually improve food security – which refers to not just access to food, but specifically to nutritious food.

“Instant noodles are high in saturated fat and sodium, which may lead to higher risks of heart disease and stroke,” said Goh Yiting, senior dietitian at Tan Tock Seng Hospital. “Such food may be loaded with calories, but aren’t high in nutrients like vitamins.”

Retiree Esther Lim is conscious of managing her diabetes and high blood pressure, and would prefer to cook her own healthier meals. But the 58-year-old – who stopped working because of leg pain and can’t walk far – was disheartened by the kind of rations she had to make do with.

Couldn’t the food donations include fresh vegetables and fresh meat? She wished.

But giving out healthier options, like brown rice instead of white, might not go down well with everyone. FFTH’s Bee Hia noted: “Change is disruptive, especially for old folks.”

OTHER MISMATCHES

Food handouts can also fail to match needs in other crucial ways.

Fion recalls meeting an elderly Malay woman who was taking care of three primary school-age grandsons, and – on top of that – battling stage 3 cancer. “There was no household income because both parents were in jail, so the family relied on charity food items,” she said.

They got regular packed meals, but the food wasn’t halal. “So, they would put the ingredients aside and eat only the white rice.”

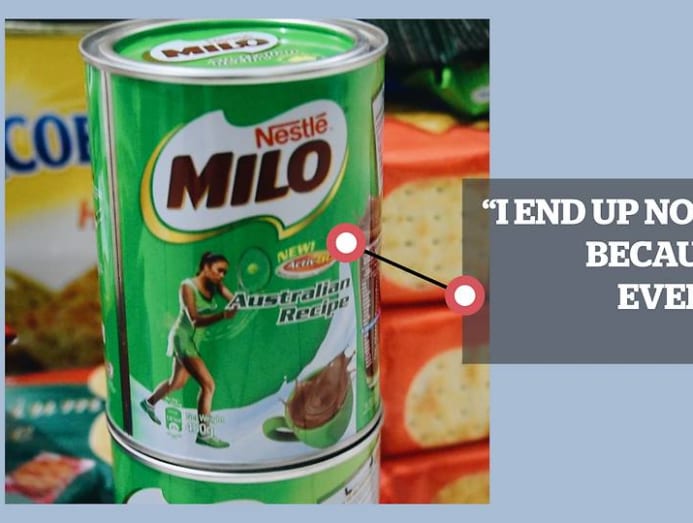

Then, there are beneficiaries’ physical limitations. Esther, for example, struggles to open tins of Milo because of the stiffness and pain in her hands. “I end up not using it,” she said. Sachet-form drink mixes would serve her better.

On one visit to Uncle Ho, CNA Insider came across a delivery of fresh carrots and sweet potatoes from one charity. There was also a large bottle of olive oil.

Healthier alternatives, for sure – but unfortunately, they were useless to Uncle Ho as he had no stove or equipment to cook them with. “I don’t know what to do with them,” he said helplessly.

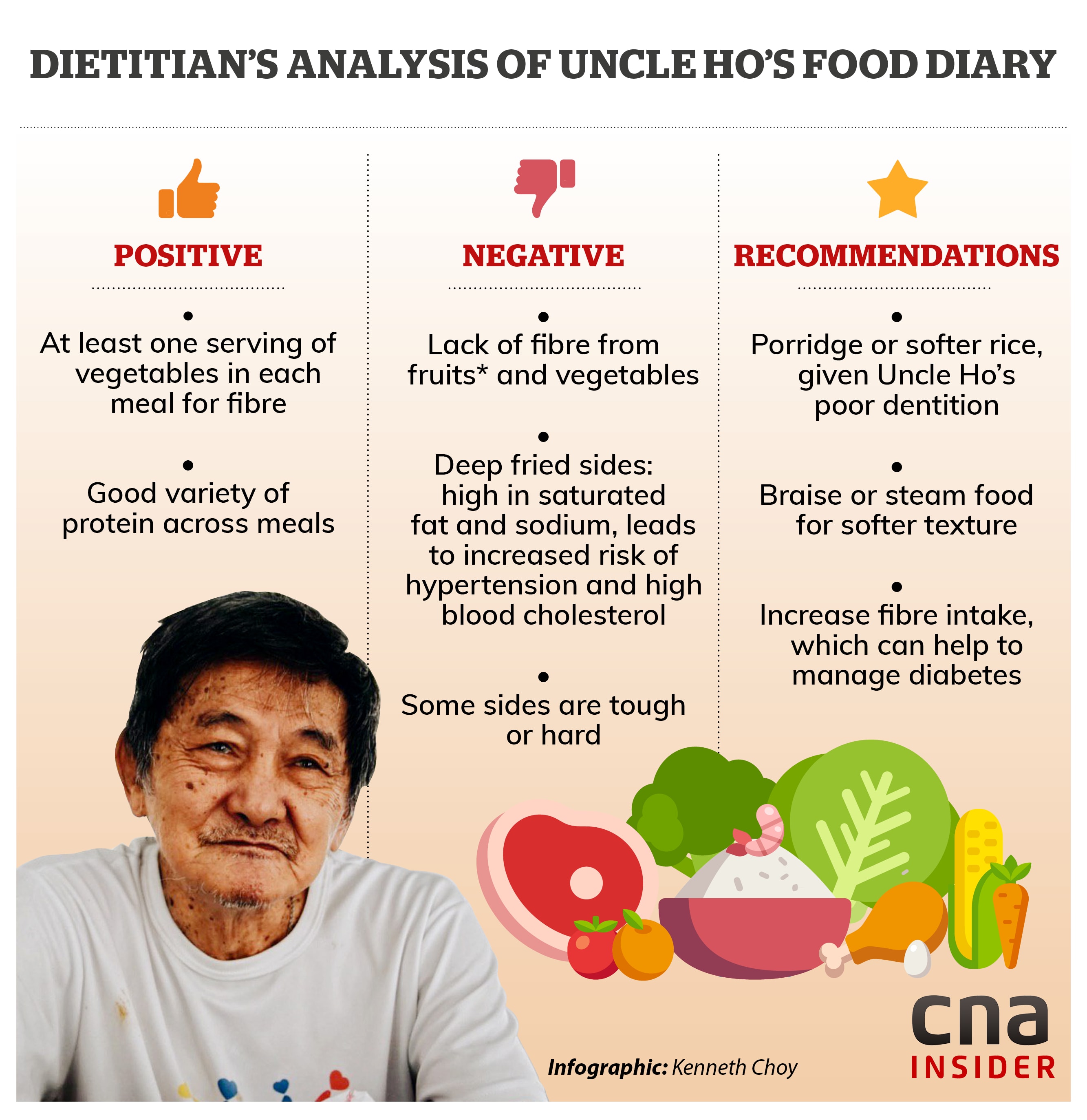

As for the cooked food he receives, dietitian Goh Yiting looked at a log of several days’ meals that CNA Insider presented her, and found them to tick the nutritional boxes in terms of vegetable servings and proteins.

But, Uncle Ho sometimes gets fried food items or meat that hasn’t been minced, which is tough for him to chew. “Just slowly eat lor,” he said. Softer foods or porridge would be ideal for him.

To better match beneficiaries’ needs, Dr Jenson Goh said, feedback channels need to be open. “But because groups often just leave the food at the door, the beneficiaries don’t tell anyone that they are overserved.”

Others might be apprehensive about giving feedback for fear of being misinterpreted, said Fion. “If they say ‘I don’t eat macaroni’, for example, people might call you ungrateful. Like, ‘I give you and you still want to choose’.”

Esther, who got a similar response when she tried to give feedback on the “bland” cooked meals by a charity kitchen, said: “We can’t give feedback because the food is free… It feels like we are beggars, what they give, we must eat.”

DONORS NEED TO GIVE BETTER

But it may not be entirely up to food charities, either. Often what determines what they can give out, are the donations they receive from the public and from companies.

Said Food Bank’s Nichol: “While charities want to feed their beneficiaries better, they won’t be able to do so if they are consistently getting unhealthy donated food. It’s therefore up to groups to communicate to their donors which items are more or less useful.”

Food From The Heart holds nearly 300 food donation drives a year for its Community Food Pack programme. Said Bee Hia: “If you give us a lot of luncheon meat, I can only give it to Chinese families. If you give us 3-in-1 Milo and coffee, I cannot give to people with diabetes.”

“People might want to give ‘fancy’ items like macaroni and cheese. But I can’t give that to seniors, they won’t know how to consume it!” she added.

She also emphasised that they cannot accept expired canned food. “We are not a dumpster, but sad to say, some donors treat us as a way to clear whatever they have at home.” The Food Bank also has received opened bottles and half-finished food items.

Charity kitchen Willing Hearts, which cooks up 6,500 free meals daily for collection or delivery, sometimes gets complaints about the lack of variety. But – aside from the fact that options are limited as it doesn’t use pork or beef out of cultural considerations – it relies on donated ingredients.

Its president Teh Eng Hua, 63, said: “Whatever people give, we use. If it’s flooding season in Malaysia, we won’t get so much green vegetables. So we’ll be eating Chinese cabbage for many days. But there’s still Chinese cabbage to eat, right?”

He thinks beneficiaries should remember that the food comes from the goodwill and “hard work” of many donors and volunteers. “Plus, it’s delivered to your doors. So we must all be thankful.”

However, with standards of living having risen in Singapore, Nichol thinks there’s room to improve on the range of food given to the needy, as “we can’t be giving the same types as 20 years ago”.

Giving beneficiaries more choice can be a double-edged sword, though, in Nizar’s experience. The FFA founder said candidly: “You get some entitlement issues… They will ask, why are the oranges this brand? Not Sunkist?”

“When I started to give milk and cheese – things the beneficiaries would not be able to afford – they started asking for better brands… if it’s not Nestle or a premium brand, they wouldn’t want.”

Donating cash instead to food charities is not a bad option – the groups, after all, can buy groceries that would meet their beneficiaries’ needs.

However, groups do feel the obligation to stretch the donor’s dollar by buying in bulk, or larger portions that are more value for dollar. Hence, why food packs are often standardised with little room for customisation; and why there’s often wasted food.

“When I first started doing charity work, I wanted to give 10kg bags of rice because why not?,” said FFTH’s Bee Hia. “But I didn’t realise that a senior living alone is going to take a very long time to finish that much rice.”

MEAL DELIVERY HICCUPS

Charity kitchens face an additional set of issues: Finding the volunteers to get cooked meals delivered every day, on time; and avoiding food spoilage.

Willing Hearts starts preparing the meals as early as 6.30am, which are then delivered across the island from 9.30am to 11.30am by some 30 to 40 volunteers.

Guidelines by the Singapore Food Agency states that cooked food should be consumed, refrigerated or frozen within two hours, but sometimes beneficiaries keep a pack until dinner time without a fridge to store it in. KHA’s Fion noted that it was “quite common” for them to find that their food had gone soggy or turned sour.

Said Willing Heart's Eng Hua: “Occasionally we hear that people do not know how to store or heat up the food properly. If it was possible to recruit more volunteers or partners, we could serve dinner in the afternoon. But for now, this is the best we can do.”

READ: ‘Not enough manpower to get food to people in need’: Food charities hit as coronavirus measures ramped up

Even the Meal-on-Wheels programme relies largely on volunteers.

TOUCH Home Care, for instance, delivers lunch by 12.30pm and dinner by 6.30pm to some 1,000 frail elderly in Toa Payoh, Ang Mo Kio and Jurong. But, on rare occasions, meeting that schedule is a challenge.

“Some volunteers would back out last minute or come too late – the meals would be close to expiration,” said Sam Ngeow, centre manager for TOUCH Home Care. “They need to be consumed within four hours of cooking. I can’t let them be delivered.”

That’s why TOUCH also gives its clients food rations every two months, so they don’t go hungry in such a situation.

Recently, one possible solution presented itself: A tie-up with Deliveroo, to deliver meals to TOUCH’s beneficiaries.

“Delivering food is what we do best… (And) we already have a steady core of riders that TOUCH can use,” said general manager Siddharth Shanker. Deliveroo also, for one month, got customers on its app to contribute a S$5-meal, raising some 1,000 meals that were delivered to 155 beneficiaries.

For folks who are ambulant, there is other generous help available that doesn’t rely on delivery services. Many grassroots and non-profit groups give out vouchers that can be redeemed at neighbourhood coffeeshops or hawker stalls.

Some F&B outlets, from restaurants to fast-food, have even stepped up to offer free meals to those in need. Others, like cafes and food courts, have pay-it-forward initiatives that (much like Deliveroo’s) rallies customers to pay for someone else’s meal.

READ: He went hungry as a teen. Now Stuff’d boss is feeding kids who can’t afford a meal

READ: Pilot to encourage public to donate meals to needy launched in Pasir Ris

But pride, and the stigma of being seen as needing charity, can stop some from coming forward – an issue Bee Hia has noted when some parents decline to let their children collect FFTH’s goodie bags at school, for fear of how their classmates might view them.

SEARCHING FOR A BETTER WAY FORWARD

For all the challenges that food assistance groups face, the good news is that a number have already set the wheels of change in motion, in ways both small and big.

Firstly, by doing what they already do, better.

FFTH, for example, now tailors its Community Food Packs: A larger quantity of items for young families, for instance. Food packs curated for diabetics and for dialysis patients (in consultation with a dietitian), featuring non-fried instant noodles, or vegetables with low-to-medium potassium levels such as french beans and cucumbers.

Esther, too, has started to get more choices from her food rations provider, in the months since CNA Insider first met her. She is now given a list to choose from, which includes frozen protein such as sausages and nuggets, with a cap of S$50 in value.

“This is better than canned food, even though it is fried,” she said.

FFTH has gone even one better by opening, in February, The Community Shop @ Mountbatten. There, 500 needy households can choose what they want for free – instead of having to accept pre-packed rations.

The charity is at the same time collecting data of their preferences, which will help to shape smarter donations.

MP Denise Phua has done something similar in the Kampong Glam precinct: A mini-mart where Comcare recipients can help themselves to donated food and groceries. “It’s important to match the needs of the recipients with what is given,” she said.

Indeed, for food groups to give better, the public needs to be educated, Bee Hia says.

“We’re hoping that people would change their mindsets and think from the perspective of the beneficiary,” she said. “Say, there’s a food drive in your child’s school, what do you do? Do you open your pantry and take out what your child doesn’t want to eat anymore?

“Or, do you take out items that you know your child enjoys, and think another child would enjoy too?”

INNOVATING TO FEED THE HUNGRY

Others aren’t waiting for a mindset change to happen, but are finding new ways to serve their clientele, with some creative thinking. Like FFA’s Nizar.

After six years of distributing food rations and cooked meals to low-income families, he believes he’s come up with a solution that will address most problems. He has turned combat rations-type MREs (meals ready to eat) into easy meals for the food insecure – only, of tastier variety.

Think buttermilk prawns, seafood fried rice and biryani: Meals more complete in nutrition than instant noodles, and quicker to prepare.

FFA produces the MREs with a shorter two-year shelf life, so that the food can be cooked in tastier ways, said Nizar. The bright-yellow retort pouches can be reheated in a microwave, but meals are also safe to consume without reheating.

“It’s especially viable for the elderly, those who can’t cook for themselves or are non-ambulant,” said Nizar.

What’s more, he said, the cost of producing these is cheaper than the cost of preparing and transporting freshly cooked meals which run the risk of spoiling. One box of 36 meals could feed an individual for weeks.

“We have to innovate, we have to adapt. Instead of going to someone’s house daily, you can bring them a box just once a month,” he said.

Then there is Food Bank’s food pantry, which has been reimagined as convenient 24-hour vending machines providing emergency rations and meals to beneficiaries in Toa Payoh. Given cash cards topped up with 50 credits, they can ‘buy’ 25 items a month.

Said Nichol: “Let’s say you really need bread, you can just tap your card to redeem; Nutella and peanut butter is free.” The aim here is to make food more accessible any time they need it – while empowering the beneficiaries with choice.

And if the vending machines idea works, Food Bank plans to introduce blast-frozen food as one of the offerings. “This brings food waste reduction to the next level. With this mode of preparation, you can give salvaged food like vegetables an extended shelf life of three to six months,” Nichol said.

TAPPING FOOD WASTE TO SOLVE HUNGER

Meanwhile, SG Food Rescue (SGFR) – which collects unsellable fresh produce from suppliers at Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre and other places – has been redistributing this excess to partners like FFA, welfare homes and charities. It has also been stocking free-for-all community fridges, which are open 24/7 at seven locations.

While the group’s primary focus is tackling food waste, SGFR founder Daniel Tay says, helping the food insecure is one way to do that. “We collect lots of food and we need people to eat it.

“Vegetables and fruits are definitely more nutritious than instant noodles. It’s about giving people better options,” he said.

Tapping the tonnes of food waste to feed the food insecure is an idea that is gathering momentum in Singapore – though it is not without its challenges.

Crucially, most charities and groups lack the chilled storage facilities to keep vegetables and fruits fresh until they can be given to the needy; and lack the manpower or resources to process and distribute these perishables fast enough.

Said Daniel: “We're doing this purely on a voluntary basis. If other government bodies and businesses step up to help fund this, we can do so much more.”

Similarly, FFTH’s Bread Run programme could do with more help to pick up leftover bread from more than 100 partner bakeries and hotels, and bring it to collection points for beneficiaries.

“We have bakeries who want to come on board, and we need more volunteers,” said Bee Hia.

And soon, there could be even greater need for logistical help.

The Singapore Food Agency (SFA) is exploring the possibility of Good Samaritan laws to provide some legal protection against liability for those who render assistance – such as hotels or restaurants that donate surplus food.

It could be a gamechanger. Food Bank’s Nichol said: “We can then encourage donors to give without fear of being sued. It would increase the range and volume of food we’d receive.”

On the downside, she said, some suppliers might then be tempted to use food charities as a “dumping ground” to avoid paying for incineration costs. Much care would also have to be taken to ensure that cooked food donations are safely handled.

Said a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment and Water Resources (MEWR): “In considering the feasibility of such laws, there is a need to strike a balance between facilitating food donation, and ensuring that food donors and distributors exercise due care and practise good hygiene when distributing donated food.”

Still, in the broader scheme of things, economist Walter Theseira questions whether re-channelling food waste and relying on volunteer power are the best ways to tackle food insecurity.

“It sends the implicit signal that if you’re low income, you only ‘deserve expired food’. I think it’s more dignified to have money to make the choice (of what to eat) yourself,” said the Nominated MP and associate professor at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

“Efforts to distribute food that is unwanted or going to expire are driven by volunteers who mean well. But many of these organisations also limit their activities to a few times a month because the reality is, they can’t find enough volunteers to reliably do it day after day,” he added.

“The universality of volunteer efforts is a big problem… What if you’ve found an area without a volunteer group? Do you set up one there, which is difficult because by definition, volunteers organise themselves organically?

“That’s why I think there is unfortunately no substitute for some kind of coordinated action and government-led effort. It’s not to denigrate the role of volunteers – but if we have a systemic problem with food insecurity among low-income individuals, it’s a problem the government is best equipped to tackle.”

A NEED FOR TRUST – AND A MAP

In 2018, officers from the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) began informally engaging several food support organisations.

It led to the establishment of a multi-agency workgroup in 2019, involving groups like Food Bank, FFA, FFTH, Willing Hearts and SGFR; and agencies such as MEWR, HPB and SFA. The idea is to provide a platform for stakeholders to collaborate on tackling food waste and food insecurity.

More communication could certainly help to tackle food aid duplication and reach more of those in need, the charities felt.

“The first thing they should be looking at is big data,” said Food Bank’s Nichol. “We know that people need help, but where are they? Who are they? This information can only be gotten from the government.”

MSF says its role in the workgroup, apart from facilitating, would include bringing in other government agencies and "pulling together data where relevant".

However, getting groups to share information with each other – such as which households each is serving – would be a challenge.

“It’s sensitive data,” said Jenson Goh, who serves as a facilitator with the workgroup. “Between the food group and the beneficiary, there is already trust built. The food insecure often face complex problems, so groups feel the need to be more careful (about their clients’ privacy).”

Nichol nonetheless believes it is important to put together a map that shows the precise locations each group’s programmes are serving. “I don’t think we should overlap each other’s territories. Let’s say if you’re already covering this area’s 1,000 households, maybe some of us should be hands off,” she said.

But is obtaining such cooperation easier said than done?

“We have heard stories from our beneficiaries that another charity organisation came knocking on their doors and asked them, ‘Can you not take the rations from Volunteer Switchboard? Can you sign up with my group?’” said Li Woon.

This sort of thing happens she says, because groups must reach certain beneficiary numbers in order to receive grants to run their programme. (One example is the Do-Good Grant by Central Singapore Community Development Council, which can cover up to S$10,000 or 80 per cent of the project start-up costs.)

FFA’s Nizar admits that competition is unavoidable. “As charities, we are always vying for eyeballs because that’s how we get donations coming in. I think people are afraid that ‘if I were to do something collectively (with others), it would dilute my ability to get funding’,” he said.

Added Nichol: “So a lot of people guard their turf very closely – and especially guard the donors.”

FINDING COMMON GROUND

Within the workgroup, there are also philosophical differences, Jenson noted. “For example, for SGFR the primary philosophy is that (food rescue) volunteers have first pick of the food waste. But groups whose philosophy is to feed the food insecure might think that that’s self-serving.”

Yet, he thinks the workgroup has made headway in coordinating efforts. For instance, the stakeholders have compiled a list of sources, such as restaurants and distribution centres, willing to contribute unwanted food.

“We’ve also mapped the food groups and their needs – so we are trying to cross-match to deconflict people who are sourcing from the same food sources.”

One project in the works involves providing distributors at Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre with a collection schedule for the various food rescue groups. A systematic approach and clearer communication to distributors, as well as between groups, could lead to more food being available to all, said Jenson.

Said an MSF spokesperson: “We are encouraged that members are open to working together to improve the charity food landscape, and look forward to deepening this collaboration.”

While it might take a while to break down silos in Singapore’s food charity landscape, Nichol is hopeful that groups can find common ground.

“We’re all in the business of helping others, so let’s do this business better – a team of charities bonding over the love of food and over the love of feeding other people,” she said.

This is the second of CNA Insider’s two-parter on food insecurity. In Part 1: Why in a food paradise, some Singaporeans are still going hungry.

HOW YOU CAN CONTRIBUTE

Free Food For All: https://freefood.org.sg

Food From The Heart: https://www.foodfromtheheart.sg

Food Bank Singapore: https://www.giving.sg/the-food-bank-singapore-ltd

Willing Hearts: http://www.willinghearts.org.sg

SG United: Various charity efforts amid the COVID-19 outbreak https://www.giving.sg/sgunited

TOUCH Community Services: To volunteer for Meals-on-Wheels delivery, call 68046565