Commentary: Phishing and other SMS scams – shouldn’t banks bear the cost?

Millions have been lost by customers but could safeguards have been put in place by banks to protect the monies of their customers? This phishing problem is a shared responsibility, Pinsent Masons partner Bryan Tan says.

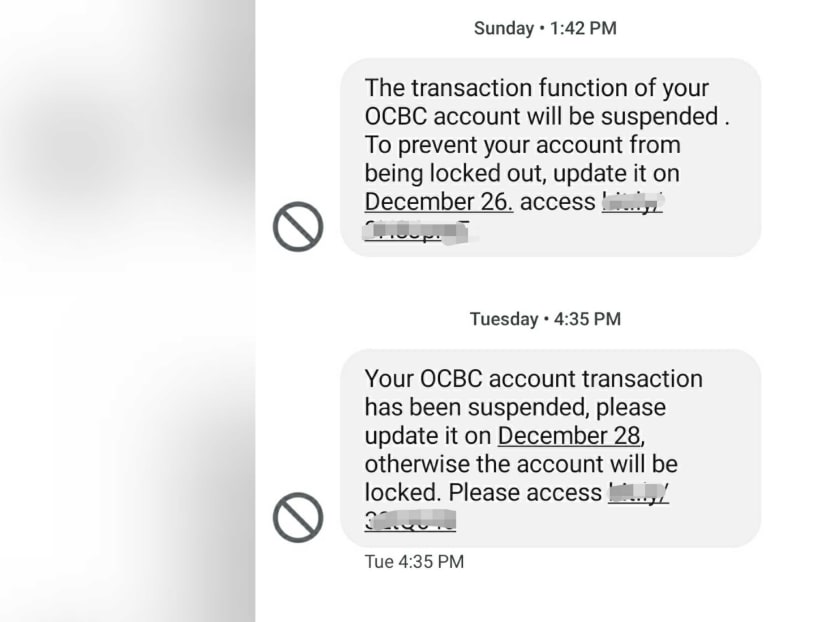

Screengrab of phishing scam messages impersonating OCBC.

SINGAPORE: In December 2021, OCBC Bank made several announcements warning about scams targeting OCBC customers.

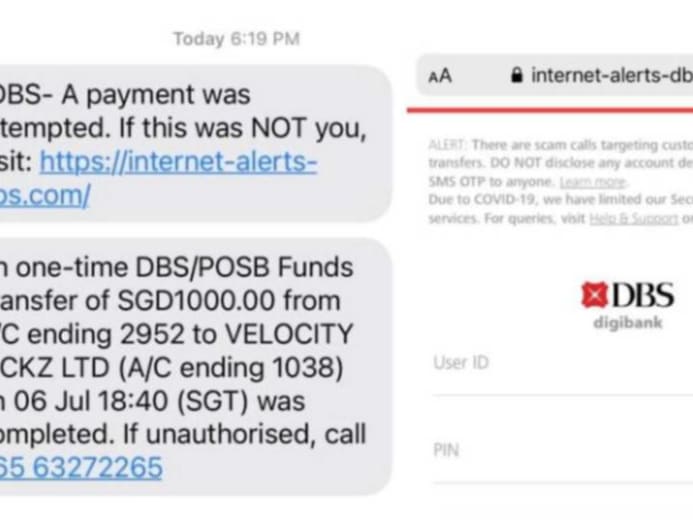

These SMSes purportedly from OCBC claimed there were issues with the recipient’s bank accounts or credit cards. But they were not actually sent from the bank.

Instead, the SMSes carried links to a fraudulent website requesting for banking information and passwords to resolve these “issues”.

Unsuspecting customers would be asked to key in sensitive bank account login information like their username, PIN and One-Time Password (OTP).

Using this information, the scammers could then transfer monies out of the affected customers’ accounts and carry out other transactions.

The scammers would reroute received monies through various, often overseas accounts, making it difficult to track their movement and even harder to recover the cash.

At least S$8.5 million have been lost in December to such scams involving OCBC, according to the Singapore Police Force.

SMISHING – A NEW KIND OF PHISHING

Public education has been said to be a key solution to stem these scams. That makes sense when these scams employ a variety of social engineering tools and techniques to trick people into handing over their login information.

Smishing, in using text messaging such as SMS to execute the attack, simulates the SMS many get from their banks from time to time notifying you of transactions made or your OTP when you log in.

The perpetrators employ deception in sending messages to users impersonating a known brand, leveraging tactics to create a heightened sense of immediacy, in masquerading as a warning of a security breach or other similar scenarios needing an urgent response, and then leading people to click on a link or download a file.

They also spoof a genuine sender’s name and short code enabling the scammer’s SMS to appear as if it originated from a legitimate sender, sometimes enabling their message to appear in the same thread as legitimate SMSes from the bank.

It’s no wonder people let their guard down.

The challenge is detecting fraudulent transactions. It is important to note that throughout the scam, the bank’s defence perimeter and security systems were secured.

The SMSes in question and the fraudulent website all operate outside of the bank’s systems. These transactions of authorising payments, adding payees and changing withdrawal limits were carried out in accordance with the bank’s procedures resembling legitimate exchanges made by consumers as they required a PIN and OTP usage.

The bank appears to be alerted to the scam only when customers begin notifying them of suspicious transfers.

DO NEW TECHNOLOGY RISKS MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES HELP?

Against the background of the digitalisation of banking services, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has, since 2002, introduced the Technology Risks Management (TRM) guidelines and has periodically updated them, the most recent being in January 2021 after the SolarWinds supply chain attacks.

The TRM guidelines say that financial institutions “should actively monitor for phishing campaigns targeting the (financial institution) and its customers”.

They further stipulate that: “Immediate action should be taken to report phishing attempts to service providers to facilitate the removal of malicious content. The (financial institution) should alert its customers of such campaigns and advise them of security measures to adopt to protect against phishing.”

Before one jumps the gun and concludes that banks have liabilities to bear when such scams happen, the guidelines also clearly stipulate the limits of their application: They “do not affect, and should not be regarded as a statement of the standard of care owed by (financial institutions) to their customers”.

“The extent and degree to which an (financial institution) implements the guidelines should be commensurate with the level of risk and complexity of the financial services offered and the technologies supporting such services. In supervising an (financial institution), the degree of observance with the spirit of the guidelines by an financial institution) is an area of consideration by MAS”.

In lawyer-speak, it means the TRM guidelines do not form the basis on which legal liabilities are determined.

It is telling that there have been no reported cases brought to the courts based on a breach of the TRM guidelines. Instead, the MAS uses compliance of the TRM standards as an area of consideration in its assessment of financial institutions – like when it assessed DBS Bank’s liabilities in 2010 outages of its online and branch banking systems.

Therefore, the determination of liabilities for the losses between the two affected parties – the bank and the customer – is not an easy one and the losses fall on customers today. This may sound painful considering how according to some reports, even bank accounts of children were wiped out.

However, unless there are laws stipulating greater responsibility on the parts of banks to address phishing, the relevant fact is that the bank’s cybersecurity, verification and processes were intact. The customer had fallen prey to the pretences of the scammers, hence, the customer bears most of this burden.

Authorities know this and have set up a task force led by MAS in July 2021 to study how to apportion liabilities of such fraudulent transactions between affected customers and financial institutions. Their findings are eagerly anticipated.

What were the implications of those changes in WhatsApp terms and conditions in 2021? CNA's Heart of the Matter explores:

PHISHING IS A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Meanwhile, more work must be done to tackle this new cybersecurity threat as the criminals are winning. I would argue this is a shared responsibility of all – government, consumers and businesses.

Clearly, the public education element is still lacking. With the pervasiveness of digitalisation at home and at work, we cannot let up on such efforts. It is evident that consumers need to learn to identify phishing attacks as a basic cyberwellness skill. Perhaps simulations should be run to identify those who still fall short. Some employers do this to identify employees who need to retake cybersecurity training.

Given that banking systems were not compromised, the natural question is whether systems outside of the bank need monitoring and what level of monitoring is appropriate.

Would this extend to policing the entire Internet for fraudulent sites mimicking a bank’s websites and monitoring SMS systems? Would this also include monitoring customers’ devices? Would this “policing” function turn into a privacy nightmare? There was swift backlash against Internet service provider SingNet in 1999 for scanning 200,000 computers for virus vulnerabilities without the knowledge of their subscribers.

Today, banks employ artificial intelligence to counter fraud on seemingly normal transactions. Would an increase in this activity offend banking confidentiality?

Perhaps a leaf can be taken out of a proposal where financial advisors in Singapore today are required to identify vulnerable customers.

In these areas, banks are required to identify the customer’s financial savviness, and take additional measures when selling to such customers.

Similarly, where a customer is identified to be digitally vulnerable (or has asked to be identified as digitally vulnerable), then the suite of digital services offered to such customers would be narrowed to exclude the real-time or super-quick transactions for large amounts. A third “key” such as Singpass might also be required.

Bryan Tan is technology and fintech partner at law firm Pinsent Masons and a former Singapore chapter president of the Internet Society.