Commentary: Can Singapore follow China’s move against the massive private tuition industry?

The straight answer is no and parent of three children in school, Cherie Tseng explains why.

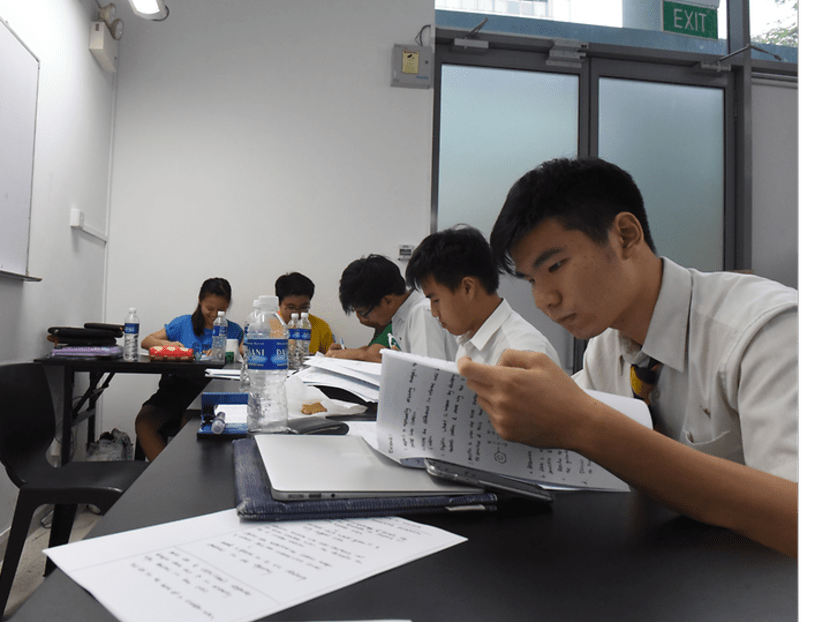

Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) students undergoing tuition for the International Baccalaureate at tuition centre Ideas Ink School in 2017. (Photo: Justin Ong)

SINGAPORE: China, in a shocking move, has moved to bar for-profit tutoring in core subjects, threatening to decimate its US$120 billion (S$162 billion) private tuition industry.

“All institutions offering tutoring on school curriculum will be registered as non-profit organisations,” CNA reported at the end of July, of the populous nation. There will also be bans on core subject tuition classes on weekends and holidays.

Over three in 10 students in China attend some version of post-school enrichment.

The pressure for children to succeed in the populous nation is so widespread, there is even a word for it: “Jiwa” or “Chicken Baby”, a term that refers to children whose lives are crammed to the hilt with enrichment classes and activities.

Heaven forbid that jiwas waste a single minute of their lives.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly then, the for-profit education sector there has come under scrutiny as part of a push to ease pressure on students and reduce the financial cost to parents – factors blamed for a drop in birth rates.

A recent New York Times story examined how China had long avoided discussing mental health, until the pandemic. Social stigma and long-term challenges remain, surely, but at least there seems to be decisive strides in the right direction to ease academic stress.

“Around the country, (Chinese) schools have expanded mental health counselling and encouraged students to take time to unwind, as the Ministry of Education has warned of a ‘post-epidemic syndrome’,” the story reports.

It is unclear if corresponding school loads and examination requirements would change given its recent announcements, but this move by the Chinese government to make tuition a non-profit sector might just be the shake-up the country needs to change its pressure-cooking-chicken-baby narrative.

CAN SINGAPORE DO THE SAME?

It is doubtful that Singapore will ever make such an audacious move. That would herald a new and vastly different world order, away from one where prestigious scholarships still look at academic scores and more broadly, when meritocracy remains a key principle for recognising individuals here.

Our version of meritocracy - and by extension how we view success - comes down to how our we do in school. It begins when we start formal schooling; if not in the form of grades, then benchmarks and a societal obsession at keeping up with our peers.

Most parents think: I have to get my child off the best starting block that my time, money and social capital can afford, so they have the best chance of success.

This means getting into top schools at the get go. The belief is that a good start will pave a smoother path, all the way to university, well-paying jobs and the proverbial Singaporean success story.

If we buy into this paradigm, then tuition is just one lever in a very interconnected eco-system. To suggest that we can simply make it go away, the way China is attempting, in my view, simply unrealistic even if it makes for exciting speculation.

If we want to lessen the use of tutors, or indeed manage the general pressures our children face, other gears in the system need to shift first.

And not just moves such as removing common topics for the year after schools have already prepped assessment papers.

The question is whether our curriculum is overloaded in the first place. If the pace of what our kids need to study is less frenetic – when kids show that they can cope with what is taught in school, then the need to keep up with extra tutoring will naturally fade away.

But this is a big cogwheel in a system where the better the grade, the greater the options for students.

Even the Direct School Admission (DSA) programme weighs heavily on achievement that is often a product of rigorous coaching programmes outside of the school system.

There are also other knock-on factors to consider. With more children coming from dual-income homes, the role of enrichment centres can solidify further – to help stand in the academic gap where parents are unable to, be it because of work or ability.

You only need to watch shows like Are You Smarter Than a Fifth-grader? to know that many successful adults are relatively divorced from the expectations of academic school life.

So many rely on excellent tutors to help their children navigate math or science, especially when PSLE exam questions can still stump us.

Tutors also give kids the learning scaffolding they need – and some need this more than others. Even if we lessen the load or changed assessment criteria, it could still be useful for some students to receive subject coaching for competency.

Would the Education Ministry consider doing away with the PSLE or implement later start times for schools to ease the pressure off students? We asked Minister of State for Education Sun Xueling in this week’s Heart of the Matter podcast.

Layer the pandemic, and the long tail of Covid whips us all.

A joint op-ed in the Straits Times by the heads of the multi-ministry task force reads: Living normally with COVID-19. We are, they say, “drawing up a road map to transit to this new normal”.

But there is nothing normal about life in this pandemic for students, or indeed, any of us. The scope of exams for our students might be adjusted, especially in major examinations, to adjust to that disruption in the short term.

But in the longer term, by and large, we expect students and parents to go on with business as usual, to demonstrate resilience and return to normalcy when restrictions lift and severe cases subside with vaccination.

RELOOKING THE ECOLOGY OF CARE IN OUR SYSTEM

Singapore has always been very good at hitting our Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). We test well – in PISA and Olympiad competitions. Even accounting for issues with delays, lapses and confusion in quarantine orders — by most pandemic related standards, we have scored well.

Yet, especially after the River Valley High School incident, there is a palpable — if still intangible sense that things are not okay with the heart of who we are as a nation.

It is akin to scoring well in one core subject—maybe even winning the book prize—but not faring quite as well in others.

And unlike the past where one subject could help raise the average, the new scoring system means that all other subjects matter too. Clearly where mental wellness is concerned, we are firmly in the “need tuition” zone.

In school, if you were weak in a topic, you could deep-dive and work on that topic until you gain competency and a good tutor helps you do that.

But for children struggling to cope with their academic load, what with added pressures of just growing up and dealing with relationships, simply dispatching more people to keep a closer eye on them is like putting a band-aid on a bleeding wound.

It ignores the general malaise in the body caused by a growing tumour that needs greater attention.

For sure, the coronavirus has exacerbated stresses and pressures in our society, but we cannot deny that the fractures and cries for help were already present – mirrored in steadily increasing calls received by the Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) and cases seen by the Institute of Mental Health.

It took the pandemic for China to finally make strides—and pivotal changes, in dealing with mental wellness by addressing the punishing academic loop they found themselves in. This is really the tip of the iceberg. But we don’t fault China for trying.

Even then, asking for less tuition or appealing to adjust our idea of what success means can only go so far, much less wishing a sledgehammer of curbs on tuition can change the DNA of a society.

In Singapore, we need to seriously consider if our quick fixes can address deeper rifts and whether it is finally time for mindsets to move away from fixating on academic achievement as that key metric of success.

Cherie Tseng is Chief Operations Officer at a local fintech company, a mother of three and editor with The Birthday Collective.