Commentary: Ambitious oil facility in Pengerang, Johor a gamble given global climate change agenda

On the one hand, Malaysia is embracing shifts bringing forth more renewables and electric vehicles. But on the other, it’s opening big oil facilities, says Renato Lima-de-Oliveira.

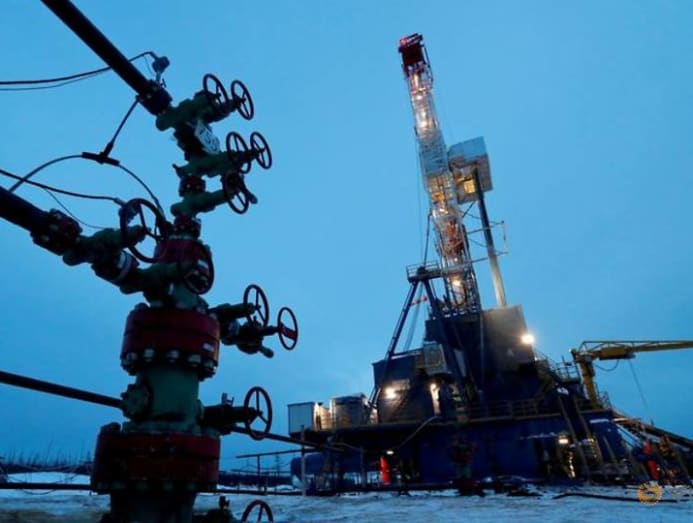

A worker prepares to transport oil pipelines to be laid for the Pengerang Gas Pipeline Project in Pengerang, Johor, Feb 4, 2015. REUTERS/Edgar Su/File Photo

KUALA LUMPUR: One of the most ambitious projects of Petronas, Malaysia’s national oil company, will soon be fully operational.

The Pengerang Integrated Complex (PIC), in the southern state of Johor, is poised to transform the country’s footprint in oil refining and petrochemical production.

Spread across 2,550 ha and the result of a US$27 billion investment in partnership with Saudi Aramco, PIC will house a new site of downstream oil operations.

However, at a time when the world is increasingly stressing the importance of green development and phasing out fossil fuels, are Malaysia and Petronas making the right bet?

READ: Malaysia's Petronas steps up investments in hydrogen as part of carbon-free energy goals

SIGNS OIL IS PAST PEAK DEMAND

There are signs oil is now in a decline. The sudden demand destruction caused by the pandemic, when oil consumption fell by a record of 8.6 million barrels per day (bpd) according to the International Energy Agency, accelerated the plans by key oil and gas (O&G) companies to wean off fossil fuels.

COVID-19 was particularly harmful because oil is primarily used in the transportation sector, which accounts for 57 per cent of total oil demand. Lockdowns are designed to force people to stay put, and this means not driving or flying.

READ: Commentary: Targeted travel restrictions needed but careful not to undermine Changi Airport's connectivity

Unsurprisingly, the financial results of O&G companies showed record losses for 2020, including Exxon (US$22.4 billion), Shell (US$21.7 billion), Petronas (US$5 billion) and most others.

Oil demand is expected to return to pre-pandemic levels by 2022, at around 100 million bpd, as vaccination rates tick upwards and movement restrictions are lifted.

However, oil as a source of energy has been under intense threat from multiple directions. Many agencies and companies now believe oil has reached peak demand or will do so in the next few years. Since the 2014 price crash, the exploration and production segment of the oil industry has not fully recovered.

A 2021 report from the Malaysia Petroleum Resource Corporation shows revenue from Malaysia’s O&G services and equipment industry has been declining, registering RM65.1 billion (US$15.5 billion) in 2019, down from over RM80 billion in 2013.

Profit before tax has been declining and was barely positive in 2019, at RM1.1 billion. Malaysia’s O&G production has been stable since 2008, with about 1.7 million barrels of oil equivalent, but capital investments have been going down: From the peak of US$10 billion in 2013 to just US$4.5 billion last year, according to Rystad Energy.

With these margin compressions, it was already challenging times for the O&G industry even before COVID-19.

The International Energy Agency has set out a pathway for countries to transform their energy sector – but how feasible is it? Find out on The Climate Conversations.

TECH AND POLITICS: HEART OF NEW THREATS TO OIL

Technological advances and politics are at the heart of the new threats to the oil industry.

Renewables are already the cheapest compared to fossil fuels in many places, after taking into account both capital cost and maintenance and fuel costs.

Modern renewables (solar photovoltaics and wind energy) have benefited from tremendous cost reduction. They have enjoyed incremental technological gains, scale economies and learning-by-doing.

Back in 2013, the construction cost of 1 kilowatt of solar PV capacity was above US$4,000, but by 2018 it was already below US$1,848, according to the US Energy Information Agency.

READ: Johor to build largest solar power plant in Southeast Asia: Sultan Ibrahim

In comparison, natural gas construction cost stayed mostly flat (US$837). But gas-fired power plants have a higher marginal cost than renewables due to fuel and higher maintenance costs.

With lower capital costs and more players competing in solar, governments can procure green energy at a declining cost. Malaysia has used auctions to buy solar energy since 2016, with prices falling to less than RM0.20.

The cheaper electricity generated by renewables is particularly attractive for electric vehicles (EVs), which have benefited from tremendous technological gains in batteries.

EVs are superior to traditional cars: They are more efficient in converting electrical energy into mechanical power, have lower maintenance costs, and can reduce urban pollution.

EVs are not yet popular in Southeast Asia, but in its Low Carbon Mobility Blueprint 2021-2030, Malaysia's Ministry of Environment and Water proposed plans to support the industry’s growth through charging infrastructure and local manufacturing.

READ: Commentary: My journey to owning an electric vehicle has been a worthy ride

Another threat to the oil industry comes from concerted political action. As societies become increasingly conscious of the negative effects greenhouse gas emissions have on the planet, there is greater public pressure in favour of more sustainable development.

And so it’s little wonder governments might promote renewables through feed-in-tariff or solar auctions and discourage fossil fuels by imposing tighter regulations and taxes on carbon emissions.

Like many countries, Malaysia has adopted policies to promote renewables – and there is a growing business ecosystem of green energy developers in the country - but has yet to adopt a carbon tax or a hard policy to phase out coal from its energy matrix.

Regardless of government policy, the private sector has also joined these efforts through sustainable investing, or initiatives like The Climate Pledge, in which companies commit to achieving net zero emissions by 2040.

Can emerging markets in Asia pivot away from fossil fuels despite growing demand? Find out on The Climate Conversations.

PETROCHEMICAL SECTOR SET TO GROW

It is clear to the industry, including oil majors like Shell, BP, Total and Petronas (which also announced a net zero by 2050 aspiration), that economics and global politics have turned in favour of renewables.

Therefore, the big picture is of an industry that is in its sunset years, because of the growing competitiveness of alternative sources and political drivers against it. However, this big picture hides heterogeneity.

If oil demand from transportation seems doomed thanks to EVs, it is a different picture for the petrochemical sector. The use of oil as a feedstock for petrochemicals, bitumen and fertilisers is likely to increase in the years to come.

In fact, based on BP’s 2020 forecast, oil demand for petrochemicals is expected to increase until 2040 before declining past current levels – even under an aggressive scenario of net zero by 2050.

Today, 9.7 million bpd are used for petrochemicals. This can grow to as much as 17.5 million bpd by 2050 if one extrapolates from past trends – or slightly reduce to 7.2 million bpd under a net-zero scenario.

At the heart of Petronas’ PIC project is the US$16 billion RAPID (or Refinery and Petrochemical Integrated Development) refinery. It will add 300,000 barrels per day of refining capacity to Malaysia, almost half of the existing capacity of six plants.

RAPID is strategically sited in a major trade route and can turn Malaysia into a net exporter of refined fuels, meeting stringent low-sulphur standards.

READ: Commentary: Oil and gas is not the sunset industry you think it is

Given its design to maximise naphtha (used as a feedstock for petrochemical production), it will be less exposed to the demand destruction EVs will bring to refineries focused on transportation fuels.

Scale and integration are critical competitive factors in the refining sector. PIC meets these criteria with its production volume and design. However, refining is an activity that traditionally requires high investment and has low margins, so operational excellence is critical.

In this regard, the RAPID project has been plagued by delays and major incidents, including two fires, one in March 2020. The long-term success of the project will depend on running it well and attracting more investors to further develop Pengerang as a petrochemical hub.

READ: Commentary: That low-carbon future for Singapore isn’t so far-fetched

The energy transition is a reality that will affect all oil-based development projects, including Pengerang. For instance, the project incorporates solar panels to generate energy for self-consumption.

However, the transition will vary by sector. Within the portfolio of assets that oil companies hold, petrochemical production will likely be among the last to be stranded.

This is good news for Pengarang, but Malaysia still needs to be ready for a world where the oil industry will take a back seat.

Renato Lima-de-Oliveira, a PhD from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), is an Assistant Professor of Business and Society at Asia School of Business in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.