Commentary: What’s behind empty supermarket shelves in the US and could it happen here?

A combination of the rapidly transmitting Omicron variant, low vaccination rates in frontline roles and a great resignation wave amid an economic restructuring has led to supermarket shortages, says Yale-NUS College’s Trisha Craig.

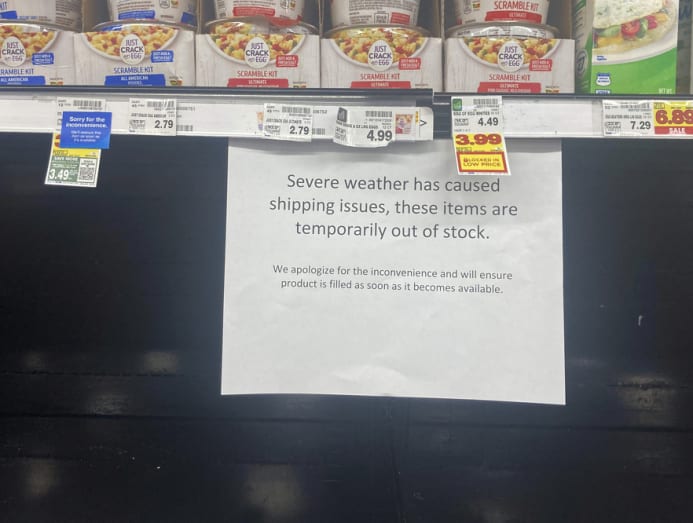

SINGAPORE: Two years into the pandemic and it’s starting to feel like deja vu for consumers in the United States and many other countries as they are again confronted by empty shelves at grocery stores.

The Omicron variant has highlighted continuing vulnerabilities countries face collectively in keeping goods stocked.

But the supply chain issues experienced now are not exactly the same as those in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis.

FEWER WORKERS TO DO THE SAME WORK

Indeed, this particularly contagious nature of the Omicron variant and its rapid spread created a perfect storm for supermarkets. But much of the problem comes down to trying to move goods with insufficient labour, rather than the shortage of goods seen earlier in the pandemic.

From mid-December until today, the virus has taken workers out of commission at all levels of the supply chain: From workers at ports unloading imported goods and those working in warehouses, to truck drivers moving the goods cross-country, to those stocking store shelves and working check-out lines.

In some sectors, production has been disrupted as well by rising COVID-19 cases that have sidelined staff. Meat shortages, for example, arise from problems at meat packing plants where there is lower slaughter capacity and not enough inspectors to certify the meat.

LOW VACCINE UPTAKE IS PART OF THE PROBLEM

Vaccine uptake, particularly the low numbers, may also exacerbate the problem.

While Omicron has shown an ability to evade immunity provided by vaccines or past infection, being vaccinated and boosted with the mRNA vaccines used in the US does confer some form of protection against the strain.

With the highly politicised nature of the vaccine, vaccination rates in the US lag behind wealthy peer countries.

Worryingly, the lowest rates are found among workers in the sectors that deal with foodstuff and consumer goods: Agriculture (49 per cent vaccinated), F&B (61 per cent), retail (64 per cent), manufacturing (64 per cent) and transportation (64 per cent), according to a market research firm Morning Consult poll.

THEN THERE’S THE GREAT RESIGNATION WAVE

The current wave of Omicron cases comes amid an underlying pandemic-induced labour shortage associated with what is known as the “Great Resignation Wave”.

Workers in frontline fields like grocery stores, restaurants and retail who have had to cope with low wages, poor benefits and often badly-behaved customers are quitting in hopes of finding less stressful and better compensated jobs.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in November 2021, a record number of Americans, 4.5 million people, quit their jobs, which amounts to 4 per cent of the workforce.

Employment in the transportation sector appears to be holding steady but trucking was one field that saw large-scale resignations early in the pandemic, losing 6 per cent of drivers.

SHIFTING CONSUMER TRENDS, RESTRUCTURING AND A BAD WINTER

Consumer demand has also shifted as a result of life during a pandemic. The emergence of Omicron means that people are eating more meals at home.

The tentative movement towards returning to the office has been slowed as people remain at home because they are sick, isolating because of exposure, unable to find test kits to determine whether they are sick, or simply staying put trying not to get infected. Restaurant dining has also taken a hit.

More home-cooked meals have increased demand for supermarket food at a time when supply chains are already under pressure.

Finally, the weather has played a role in the shortages we currently see. Harsh winter storm weather, particularly across the Midwest and Northeast US, has not only caused delivery delays of goods, but also pushed consumers towards panic-buying as they try to stock up on essentials.

Beyond normal, seasonal weather issues, some analysts point to climate change and the increasing frequency and severity of storms as wreaking havoc with supply chains.

The US is not the only part of the world facing Omicron-related supply chain difficulties. Australians are seeing similar shortages in supermarkets as the virus has spread rapidly through the workforce.

Most of Australia’s food and agriculture products are for the export market to Asia, so some knock-on effects are expected across the Asia Pacific.

Hong Kong in particular is bracing for some short supply. In addition to the supply chain issues everyone is facing, the city imports most of its food and is pursuing a “zero COVID” policy.

Flights into the city have been dramatically cut with a resulting steep decline in cargo space. Fewer imports coming during the Lunar New Year peak period demand all but guarantee some bare shelves.

Like Hong Kong, Singapore imports 90 per cent of the food it consumes. However, the city state may face fewer problems of food shortage as government policy since the beginning of the pandemic has been to protect the resiliency of the supply chain.

It has worked closely with Malaysia, the largest food exporter to Singapore, and other ASEAN nations to ensure a flow of goods while also, as researchers have highlighted, releasing food from its strategic stockpile and increasing local production by investing in industries like vertical farming.

OMICRON WOES MIGHT BE OVER BY MARCH?

Still, many industry analysts see the severe shortage problem around the world as temporary with the potential for small, sporadic disruptions.

The fast-moving Omicron variant appears to peak quickly and mean relatively mild illness for those who are vaccinated. There is a sense that by March, Omicron will have spent itself and supply chains will decongest. Yet that may be an overly optimistic assessment.

The World Health Organization has pointed out how new waves of the virus are likely, particularly because low vaccination rates worldwide give it the opportunity to mutate in unknown ways.

One key to solving this lies in vaccinations. It is imperative that the global inequities in vaccine availability are addressed, with rich countries making more of an effort to ensure supplies to emerging nations.

In the longer term, the development of a universal coronavirus vaccine could obviate the need for constant vaccination campaigns.

Given the vaccine hesitancy that has taken hold in many parts of the world, policymakers may still face challenges hitting population vaccination targets.

The current disruptions have also shown that jobs for those in the supply chain need to improve. Better working conditions, not just higher salaries, would allow workers to be better protected from the virus and to recover from it without loss of income, helping to retain employees critical to ensuring that goods are available.

Looking somewhat farther ahead, greater automation and, in some cases localisation, in the supply chain, particularly with some thought to mitigating the likely effects of climate change in coming decades, may help reduce the frequency with which consumers face the prospect of empty shelves.

Trisha Craig is Vice President (Engagement) and Senior Lecturer of Social Sciences (Global Affairs) at Yale-NUS College. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not represent the views and opinions of Yale-NUS College or any of its subsidiaries or affiliates.