Commentary: For workers, quitting a job is all about taking back control

Faced with the option of diving into the uncertainty of quitting one’s job, or the certainty of drowning in one’s work, many are choosing to jump, says documentary storyteller OKJ.

SINGAPORE: "I've quit my job".

It's a statement that is becoming increasingly common in our society.

What was once a sign of resignation, and perhaps even something that was to be frowned upon, is now increasingly viewed as a necessary act to gain back control of one's life and circumstances.

Arguably, it is more intriguing that stereotypically kiasi (“scared to die”) Singaporeans are taking such leaps of faith with no guarantees and at great personal costs.

QUIT YOUR JOB OR DROWN IN IT

Taking a leap of faith at any life stage can be a vulnerable and harrowing experience. But one may be compelled to dive head-first into uncertainty when the alternative is the seeming certainty of drowning.

And drowning in the proverbial sense is all too familiar to many of us in this "new normal", with increasing demands from the workplace to adapt, pivot and upskill.

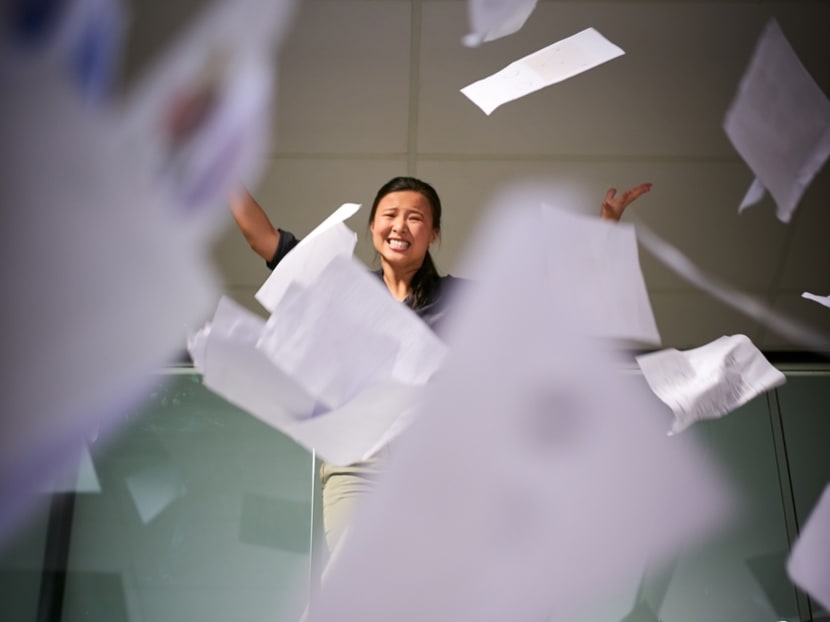

For a case in point of a job role that keeps expanding, look no further than teachers. Their workload has "more than doubled" since the pandemic, said Minister for Education Chan Chun Sing in Parliament.

He cited a key example of the need to prepare more than two sets of lesson plans for seamless switches between in-person lessons to home-based learnings – a unique necessity born out of the pandemic, which is that the show must go on, however difficult.

While pioneering new ways of interacting with students, some teachers had to accommodate a completely new system of banding and scoring, all while bearing the burdens from the psychological toll that this crisis has had on the young and their parents.

COVID-19 may have changed many facets of our lives, but it does not change the fact there are still only 24 hours in a day.

This pressure on our teachers – to go beyond their job scope and beyond quantifiable measures of sacrifice for the sake of people and country – has been felt amongst many other professions.

Senior Minister of State for Health Janil Puthucheary revealed that 1,500 healthcare workers resigned in the first half of 2021 compared to about 2,000 annually pre-pandemic.

This is perhaps a sign of the road ahead and the phenomenon known as the "Great Resignation".

BEHIND THE GREAT RESIGNATION

Texas A&M University Professor Anthony Klotz coined the term "Great Resignation" to describe what appears to be a spate of resignations in recent months, a natural conclusion of delayed decisions to resign in 2020 in addition to pandemic-related epiphanies.

In Singapore, Microsoft's 2021 Work Trend Index indicates that 49 per cent of the local workforce would consider leaving their employers this year. Alarming as it is, when read in the context of other findings made this year, this may come as no surprise.

An Oracle survey found nearly seven out of 10 Singaporeans felt this year to be the most stressful at work and a Kisi's Global Work-Life Balance Index ranked Singapore as the second most overworked city in the world in 2021, just behind Hong Kong.

Such sentiments are not missed by the Government, with Labour MP Melvin Yong proposing in October 2020 a "right to disconnect".

In a review of COVID-19’s impact on mental health, the Institute of Mental Health found 8.7 per cent of the surveyed Singapore population met the criteria for clinical depression, 9.4 per cent for anxiety, and 9.3 per cent for mid to severe stress.

It identified gaps such as sub-optimal mental health resources and a lack of trained professionals in meeting the demands of the workforce.

However, to simply pin the blame on COVID-19 for an impending "Great Resignation" may be misplaced, because while a blaze may be caused with a spark, it cannot be ignited without tinder.

AN UNSTABLE BARTER BETWEEN EMPLOYERS AND WORKERS

Before the COVID-19 era, there had already been signs that pointed us towards a destabilising workplace culture in Singapore.

Working within one's stipulated working hours was agreed upon in contract but people were expected to answer the call of duty if work bled outside of 9am to 6pm.

Listen to HR experts explain what’s behind worker unhappiness despite greater attention on workplace well-being and what managers should do on CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast:

NUS Business School's Dr Wu Pei Chuan highlighted in a CNA commentary that job satisfaction has been low, at less than 40 per cent, since 2017.

One might think such sacrifices can be best compensated with wages and other material gains, but it seems the modern workforce values other aspects of life.

In a 2021 Singapore's 100 Leading Graduate Employers survey on 13,989 undergraduates and recent graduates, 61.5 per cent of its respondents believed that personal fulfilment is more important than a large pay slip.

But perhaps what is more telling is that 72.7 per cent of respondents are prepared to accept salary cuts in the course of their career.

A job may entail an exchange of value, but that value is no longer measured in mere dollars.

TAKING BACK CONTROL

There seems to be a reckoning on the horizon as Singapore enters the third year of the pandemic.

Employers in Singapore are eager to attract and retain talent. They might be willing to meet the evolving needs and wants of their staff, as the demands and expectations of a hybrid workplace change too.

But those who choose to resign might not be doing so to look for better bosses. As a documentary storyteller, I have interviewed many who are considering resigning from their jobs without a Plan B – not as an act of giving up but to forge new possibilities.

The grand narrative throughout this pandemic is that in order to survive, one has to adapt, dare to learn anew, and in doing so, emerge stronger. It is so commonly applied in the corporate context, that it would be ironic to deem such leaps of faith as senseless in a personal context.

Quitting without any roles lined up will not be feasible for everyone and it’s up to individuals to weigh their options carefully.

But it is this pragmatism that should also spur us as a community to share our experiences from the “Great Resignation”. Because as we collectively grow from the lessons, the less naïve we will be about it.

All things considered, perhaps this is part of the light at the end of the tunnel that we are still navigating through.

Ong Kah Jing (OKJ) is a documentary storyteller who aspires to do justice to stories told.