Commentary: 11.11 sales are a symptom of the greater disease of mindless consumerism

Big sales events like 10.10 or 11.11 singles day sales may excite shoppers and net billions in profits for online retailers but if we don’t stop this insatiable need to consume, all of us are in trouble, says climate activist Ho Xiang Tian.

Workers sort out parcels for delivery in Beijing on Jul 14, 2021. (File photo: AP/Ng Han Guan)

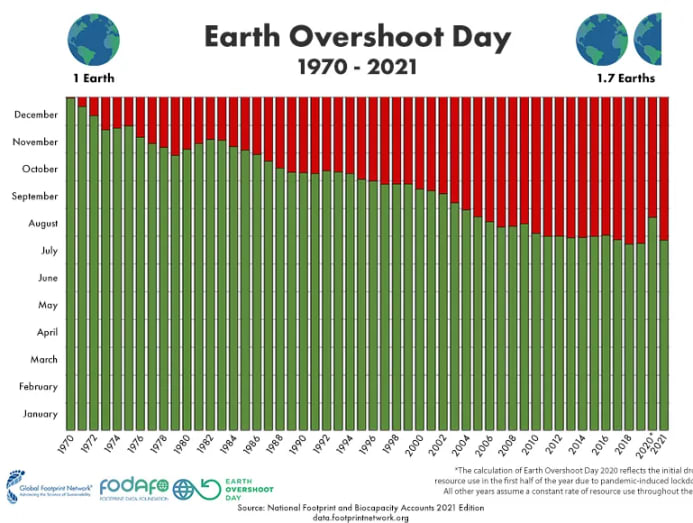

SINGAPORE: There is a little-known tracker called Earth Overshoot Day, and it gives us a sense of resources humans use.

Data is calculated based on how fast people consume resources such as energy, timber and paper, and food and fibre. Consumption and waste products generated are then compared with how fast nature can absorb our waste and generate new resources.

Based on this, it gives a date where we’ve gone over the threshold – and used up the entire year’s worth of resources.

In a way it tells us when we’ve used up all the rice in the larder which were meant to last a year.

In 1970, Earth Overshoot Day was on December 30. This year, it happened on Jul 29.

The date has been trending earlier ever since.

It also tracks individual countries and Singapore’s resource consumption per capita ranks at 24 in the world, with our 2021 Overshoot Day falling on Apr 10.

It ranks second in ASEAN, just behind Brunei whose Earth Overshoot Day falls two days earlier. In comparison, Malaysia’s is more than a month after Singapore’s, on May 30, while Indonesia’s is Dec 18.

What this shows is there’s huge room for reducing Singapore’s resource consumption, and to me, online shopping platforms are a good place to start.

Unlike most other business activities needed for essential living (driving, eating, using energy), retail shopping can encourage mindless consumerism because there’s a possibility, we buy things we don’t need.

ENTER THE RISE OF ONLINE SALES

Over the years, the 11.11 sales in Singapore have been doing better year on year. Even in 2020, when COVID-19 hit hard. Shopee for example saw 200 million items sold on 11.11 last year compared to 70 million items in 2019.

Alibaba’s gross merchandise volume on 11.11 from 2011 to 2020 has been exponential, from US$0.82 billion (S$1.1 billion) in 2011 to US$74.1 billion in 2020.

Aside from these big events, flash sales happen every month – new jingles from various online shopping platforms appear regularly, enticing consumers to “shop now” and “add to cart”.

There are attractive lucky draws. Some involve million-dollar condominiums and social media influencers go all out to get their followers to play games so they can win prizes.

Of course, the market works as it does – the aim of business is to make money and online shopping platforms will do whatever they can to drive up sales and increase market share.

It is good for the bottom line and it pays for hundreds of thousands of jobs. But this exponential growth on the back of a new age of mindless buying comes at a huge expense to the planet and unfortunately, we have started paying for it.

WHEN IT’S BAD FOR THE PLANET, IT’S BAD FOR US

Some platforms attempt to reduce their environmental impacts through “green packaging” options, but “green packaging” can differ according to each country’s context.

In Singapore, where all waste is sent for incineration, biodegradable packaging or other “eco-friendly” packaging in place of plastic packaging for online purchases is not necessarily more environmentally friendly.

A study commissioned by NEA showed that the lifecycle costs of plastic bags and other biodegradable bags have different impacts, and one is not better than the other in Singapore’s context.

Here, when waste is incinerated first before landfilling, the benefits of biodegradable items literally go up in smoke, and it’s the upstream impacts in the item’s lifecycle that determines how environmentally damaging it is.

The other issue is many online shopping platforms do not have a sustainability policy or a sustainable procurement policy, and do not track and report on their carbon emissions and environmental footprint.

When you buy a mass-produced piece of jewellery or a blouse which costs S$20 or less, it is a bargain because of the price. But consider all the other things that we don’t see. The plastic and paper packaging it comes in is one.

Then calculate the route a typical item like that takes to reach you. Likely produced in an Asian factory, it sits on a ship for weeks which requires fuel which in turn releases harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases.

Then it goes into a distribution centre to be sorted, then into a delivery vehicle, to be sent to your home.

In other words, each item has an environmental impact, including water and chemicals used to create the raw material, carbon emissions from energy to create and transport it, and land use impacts from mining or growing the raw material, and from disposal of the item.

Granted, these apply to other goods and services we consume too – but here, it is the sheer volume of items produced, sold and shipped that adds emissions to an already stressed planet.

Most online platforms also have a generous return policy and this can compound wastefulness – you can buy 10 things and return nine of them for low or no cost.

Typical e-commerce return rates are about 20 to 30 per cent, and in the US, an estimated 20 to 30 per cent of that is dumped. In Singapore, these numbers aren’t available, but it is difficult to imagine the items being returned to their overseas sources and being resold again.

How do staggering 11.11 sales figures sit with a growing consciousness about waste and sustainability? We ask a marketing professor and Lazada's Chief Business Officer on Heart of the Matter:

THROWAWAY CULTURE

There is a phrase that goes “You can’t manage what you don’t measure”, and it applies to online shopping platforms.

Without a clear sustainability policy, companies can’t measure their environmental impacts and consequently cannot reduce them although many are now seeing the need to change practices where they can.

But people are also a contributing factor to this.

Many of the products are bought for novelty or in the spur of the moment but quickly discarded or set aside.

Or things are poorly manufactured and of low-quality, which means they stop functioning as intended and eventually end up in the bin. In Singapore, once thrown out, these items are incinerated, and their ashes are sent to Semakau landfill.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

According to the Singapore Green Plan 2030, Singapore aims to reduce the per capita waste to landfill by 30 per cent by 2030. Increasing recycling rates will help but reducing the amount of waste generated in the first place is even more important in reaching this goal, especially as Semakau Landfill is expected to be full by 2035.

It may be an impossible idea, but perhaps limiting the amount of advertising from online shopping platforms may help. In addition to offering greater recycling options, making returns less convenient could be another way to discourage excessive purchases.

One company worth considering is Patagonia. Instead of encouraging consumers to buy more on Black Friday in 2013, it encouraged customers to repair its products instead, and has previously run advertisements saying: “Don’t buy this jacket”.

When it comes to a capitalist economy, it is wishful thinking to hope businesses will change their practices if it means less revenue. So, regulation could be key to reducing the impacts from online shopping platforms.

Higher carbon taxes in places where the items are manufactured could lead to increased costs even though it is possible that factories would be relocated to more affordable places unless a global agreement on carbon taxes is made.

But if businesses are taxed based on their emissions and footprint – and costs cascade down to consumers, then people may think twice before buying.

The concept of Extended Producer Responsibility could also be another way to curb excessive sales. If companies were responsible for collecting and ensuring proper recycling of products, the items listed and promoted on the platforms would quickly shift to those that are easier to recycle.

Unfortunately, the current Extended Producer Responsibility framework in Singapore is only limited to e-waste now and packaging waste by 2025, though that may change in the future.

For now, we can do our part to scale back resource consumption and push our Earth Overshoot Day to Dec 31 or beyond, and to extend Semakau’s lifespan to beyond 2035.

But societal mindsets about our consumerist culture must shift and online shopping platforms can play a role by not encouraging this mindless consumption too.

Ho Xiang Tian is the co-founder of informal environmental group LepakInSG.