Meet the woman who customises unique mahjong tiles in Hong Kong

“Mahjong craftsmanship is very much a cultural creation of Hong Kong. Very few people here still work their craft. I know that if I do not work hard to tell their stories, it will be lost,” says Karen Aruba, a third-generation member of a mahjong tile making family.

Karen Aruba and her father Ricky Cheung (Photo: Threesixzero Productions)

As any mahjong player knows, the “feel” of the tiles can make a huge impact on one’s enjoyment of the game. These days, almost all mahjong sets are commercially made by machines.

But in Hong Kong, mahjong artisan Karen Aruba is striving to revive the almost lost craft of making mahjong tiles by hand. A third-generation member of a mahjong tile making family, she grew up during the days when her entire family was involved in each step of the manufacturing process.

“As a kid, I saw my family members work hard at their craft. But at a later stage, everyone realised that mahjong tiles could be machine-made. My family really liked carving mahjong tiles so when the industry declined, I felt it was a big shame,” she said.

She founded Karen Aruba Art in 2016 to design and create mahjong sets in the hopes of reviving interest in this aspect of Hong Kong’s cultural heritage. In 2014, the craft was listed as an intangible cultural heritage of the city but there are few artisans left practicing this trade today.

“Mahjong craftsmanship is very much a cultural creation of Hong Kong. Very few people here still work their craft. If I do not work hard to tell their stories, it will be lost,” she said.

With so few craftsmen left in Hong Kong, she had to persuade her father Ricky Cheung to come out of retirement to return to the craft he loved.

“I really want to return to our roots so I focused more on getting people to know the stories and meaning behind our mahjong tiles because a master craftsman has spent his life engraving or colouring these beautiful tiles,” she said.

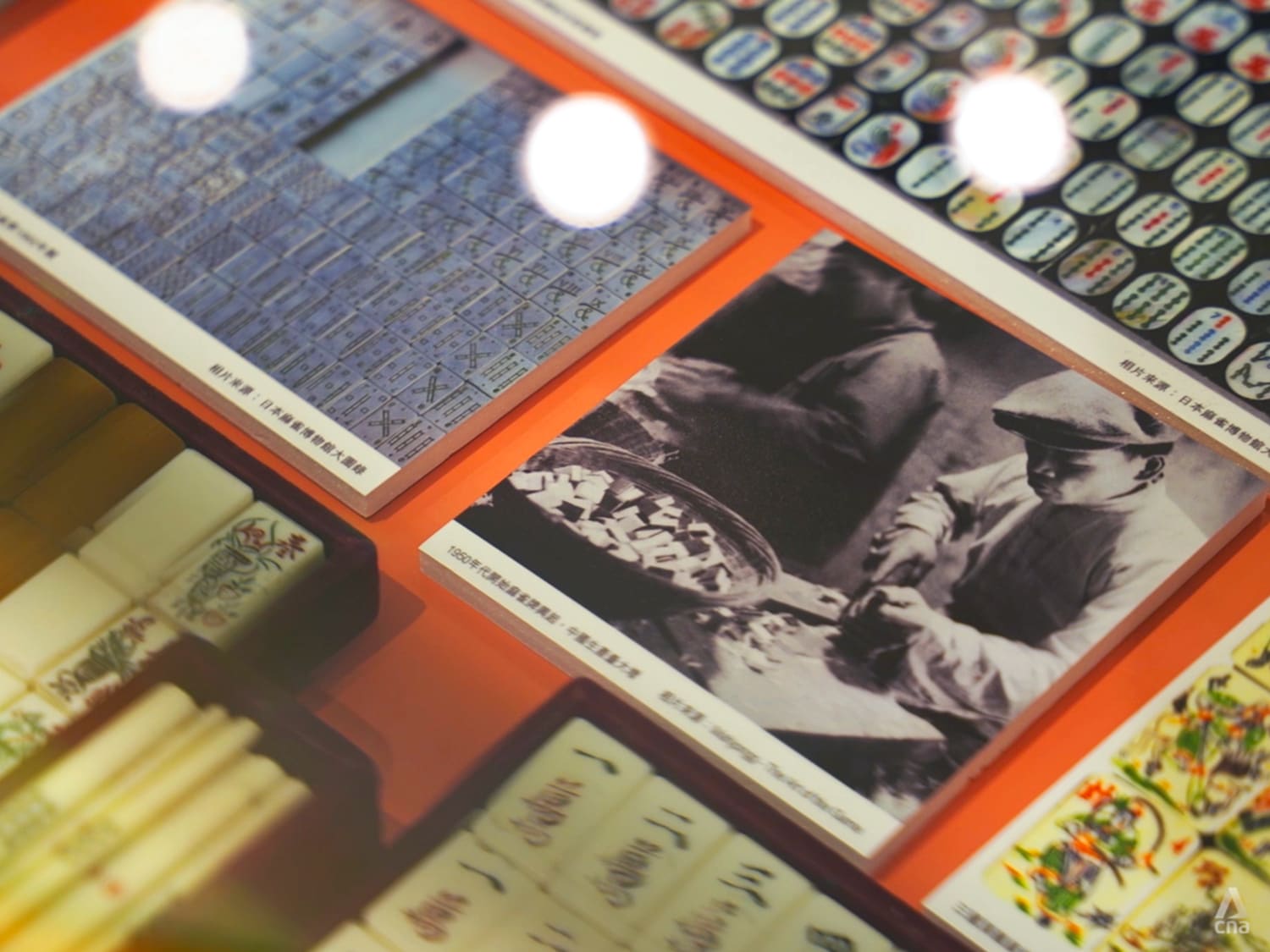

During her research on the history of local mahjong, Aruba realised that her family did not even leave photographs or materials for her to work with and her grandmother had accidentally thrown away the tools.

“I was having a difficult time when I met some masters. I asked them if they could lend me the tools. After they heard my grandfather's name, they gave me their tools because they thought I could pass on their memories and craft on. I was so touched at that moment,” she said.

It was then that she realised there is a larger purpose to her revival of this craft. “I feel that every creation has a story behind it ‒ about how people work together to make something, which then brings out the intrinsic value of the art and craft,” she said.

Learning the skill of carving even a single stroke beautifully can take a long time to master, said Cheung, a master craftsman. “Hand-made mahjong tiles is a skill that is almost lost in Hong Kong. Learning the skill takes a very long time. You need a few years to master how to just carve a tile by hand,” he said.

Even with his years of experience, he did not feel confident about coming out of retirement. “But I was drawn by her beautiful designs when she asked me to try to carve some simple characters,” he said. “I had not used my skills for more than 10 years, but I tried anyway. The response was surprisingly good and we won an award. That gave me more confidence to get back to the craft.”

Mahjong tile making is so rare that even the tools such as the drills, scrapers and lamps are impossible to come by ‒ they cannot be bought and have to be made by hand.

“The steel rods need to be ground flat and the edges sharpened (before they can be used for engraving). A manual drill bit, which we have to shape, is used to make the Circle characters and then we use a scraper to the Bamboo characters before the final touch-up,” he said.

This is a painstaking process and it can take Cheung one to two weeks to complete a set of 144 tiles. He used to be able to carve a few sets a day but he now only makes one set at a time. He said, “I used to have good eyesight, but now my eyes get worn out easily. I still want to take this seriously and carve these tiles beautifully.”

A few years ago, Aruba began to experiment with creating unique tile designs that featured different locations in Hong Kong. That was when she noticed there was a demand from mahjong lovers overseas for their handcrafted sets. A university professor even asked for Greenland-themed mahjong tiles, inspiring her to design more locality-based sets like a Canada set and a favourite of hers ‒ a Hong Kong set.

“I really like to draw the city of Hong Kong and harbourfront scenes because I feel that amidst the bustle, there are many warm human stories and sentimentality for the city’s past, so I like to use different lines of varying thickness to express the vitality of the city,” she said.

“Mahjong has a long history in Hong Kong, so I felt I should include things that resonate with locals and designs that make them happy like dim sum or street stalls or street scenes.”

She and her father also run exhibitions and workshops to educate people about tile-making and create souvenirs and decor items to appeal to a wider group of customers. All these efforts to document the skills of the trade and to spread awareness about the craft is slowly but surely paying off.

Meet Karen Aruba, a third-generation member of a mahjong tile making family, who wants to revive this dying craft to preserve this cultural heritage.

She said: “My father thought it was amazing that many people like the things he made. During his time, hand-carved mahjong tiles was not something people would cherish and it was considered a thing of the past. Suddenly, people support his craft, so he feels this is very special and has become more motivated to work hard with me.”