IN FOCUS: ‘Boomer, snowflake, oppie, pappie’ - unpacking the growing social media polarisation in Singapore

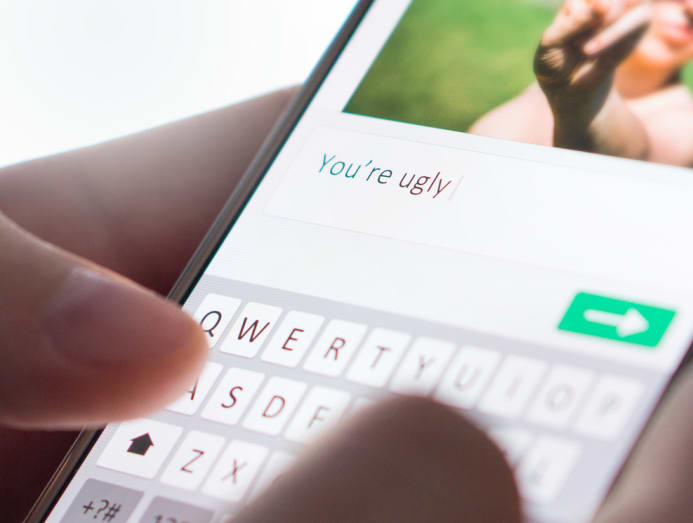

Is it possible to have a civil discussion online when you disagree with each other without getting "cancelled"? Or does social media inadvertently turn everyone into a troll, complete with name-calling and snarky "clapbacks"? CNA dives down the rabbit hole of online discourse for answers.

Moderation seems so hard to find on both sides, and emotional reactions are aplenty in online discussions, shared individuals who spoke with CNA.

- Finding moderate comments can be difficult, whether in the pro- or anti-establishment camp, as many discussions get emotional or turn into personal attacks very quickly.

- Snap judgments are often effectively expressed through online slang, such as "boomer" and "snowflake", but language can also hinder communication, especially if these terms lead to trolling.

- Beyond government policies and hate speech laws by technology companies, civil online discourse boils down to individual action.

SINGAPORE: To concoct a typical example of social media discourse in Singapore, start with the key ingredient - a thorny issue.

Think racism, immigration, gender equality, meritocracy or, in more recent times, getting vaccinated.

Sometimes, it could be something that might seem a little less heavy, such as whether the McDonald’s BTS meal or Michelin-starred hawker food is overrated.

What begins as an exchange of views quickly morphs into a minefield of sarcasm and snark, with comebacks punctuated with Internet slang, perhaps to generate "likes" and retweets or to simply stir the controversy.

“The reason why I don't vote oppies.”

“This is so tone-deaf. Check your privilege, boomer.”

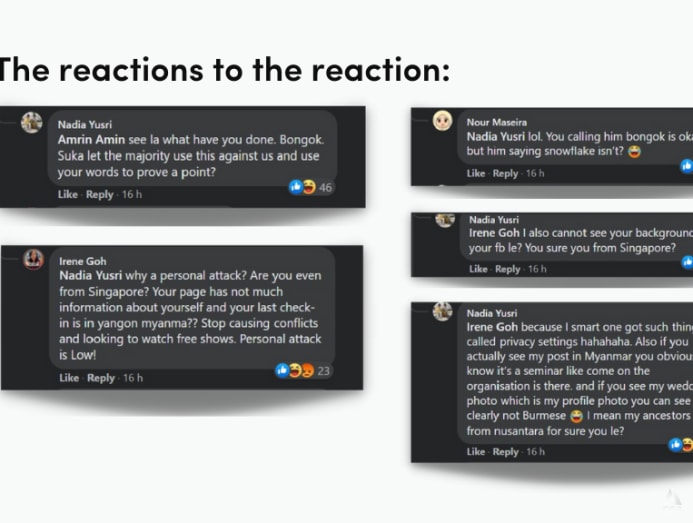

In June, the People's Action Party's (PAP) Amrin Amin said on his Facebook page, in response to a commenter, “Don’t take offence too easily, snowflake.”

The commenter had said that even though Mr Amrin didn’t think the People’s Association (PA) misusing a Malay couple’s wedding photo for a Hari Raya standee was racist, it didn’t mean other minorities agreed with him.

Mr Amrin’s "snowflake" comment drew flak. One commenter replied, “See la what you have done. Bongok", using a term that implies someone is stupid or dumb.

Replying to the "bongok" comment, another commenter defended Mr Amrin: “Why a personal attack? Are you even from Singapore? Your page has not much information about yourself and your last check-in is in Yangon, Myanmar??”

Several comments down, no one was discussing the original incident anymore.

Such a turn in discussion, with polarised views and insults being hurled, is not uncommon in Singapore. It is also a situation that some people perceive to be getting worse.

According to a YouGov survey conducted for CNA among 1,055 respondents, 64 per cent indicated that they have observed increased polarisation of views online in Singapore in the last five years.

The survey defined polarisation of views as people who hold differing opinions becoming divided into contrasting groups based on these views, where the views they hold drive these groups further apart over time, such as through personal attacks towards each other.

The same survey showed that 27 per cent of respondents had become involved in personal attacks - on the giving end, receiving end, or both - when trying to argue an issue online.

Speaking to CNA over Zoom, MP Tin Pei Ling (PAP-MacPherson), who is also the chairperson of the Government Parliamentary Committee on Communications and Information, said that she has seen a rise in polarising views online.

“I see some beginning of that phenomenon where you have groups of people on the same issue, but at very far ends of the spectrum. Each side comments with a certain conviction, and some even have a personal anecdote that they share to enrich the story or their position,” she said.

Referring to recent racist incidents as an example of what triggers polarising responses, Ms Tin said getting upset over “brazen behaviour” is “a good sign”. But excessively polarising responses can “chip away” at Singapore’s model of a multicultural, multiracial society.

“The thing is, these subtle changes over time - you don’t notice it on a day-to-day basis, but one day when you reach the tipping point, you realise, my gosh, there’s so much misunderstanding and such deep-seated emotions and undercurrent, it might be too difficult to address,” she said.

WHAT DRIVES POLARISATION?

The growing level of education in Singapore is one factor that has resulted in “more overt and pronounced” polarisation, shared Lim Sun Sun, Professor of Communication and Technology at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD).

“People are more exposed to different viewpoints from around the world. People have also gotten more comfortable with asserting their opinions on social media platforms. This convergence of multiple factors has actually led to greater expression of political views in the online space.”

And while some may assume that age is an important factor in influencing people’s viewpoints, Prof Lim argued that this is a reductionist perspective.

“Many people in the boomer category (people born in the 1950s and 60s) are very liberal, just like there are young people who have very right-wing, conservative viewpoints, possibly because of religious beliefs. The more meaningful variable to think about would be education.”

Related:

MODERATE VIEWS LACKING, IN-FIGHTING A CONCERN

Respondents in the YouGov survey were also asked to name public personalities or platforms in Singapore that they felt encouraged polarised views.

The top two individuals identified were former Nominated MP Calvin Cheng and blogger Wendy Cheng (better known as Xiaxue), while the most mentioned online platforms were The Online Citizen and Wake Up, Singapore.

One of Mr Cheng’s recent Facebook posts that drew polarising comments was written after the PA incident that had evoked Mr Amrin’s "snowflake" response. He said: “Extremists in Singapore want Chinese people to feel guilty about being Chinese, because they have ‘Chinese privilege’. This is an extreme ideology imported from America.”

One commenter supported Mr Cheng: “Certain minorities are tactically playing the ‘victim’.”

A couple of commenters asked him to explain his “flippant and incendiary” comment, while another suggested that he “try being a minority first then understand what they go through”.

In response to such retorts, another commenter jumped in with a defence: “People like Snowflake Sarah who like to play victim and clearly want to link everything to racism. PA, vendor, MP all already apologised for that culturally insensitive and stupid mistake yet she just wants to stir and stir to cause more hatred and conflict.”

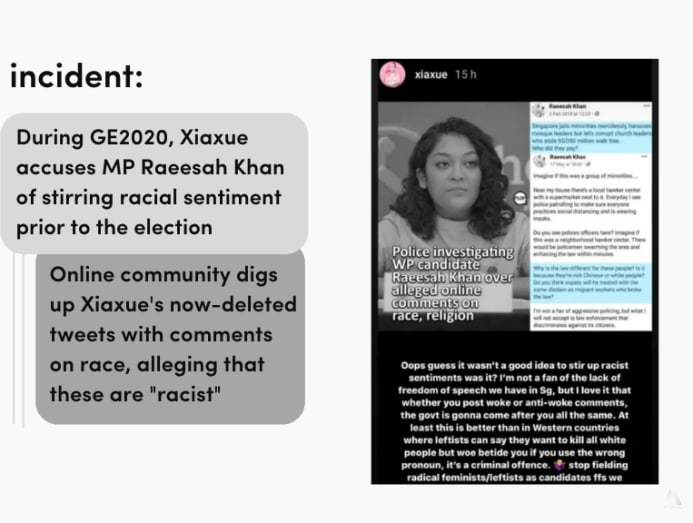

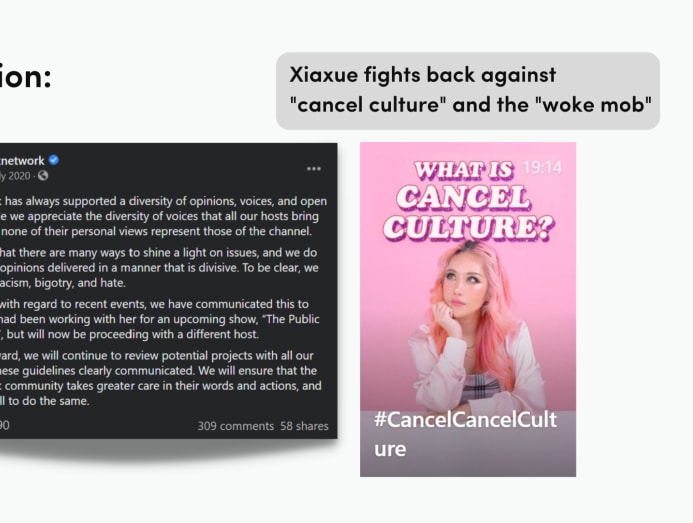

As for Ms Wendy Cheng (Xiaxue), the social media influencer’s own allegedly racist posts were dug up when she said on Instagram that MP Raeesah Khan (WP-Sengkang) was stirring racist sentiment in the run-up to the 2020 General Election.

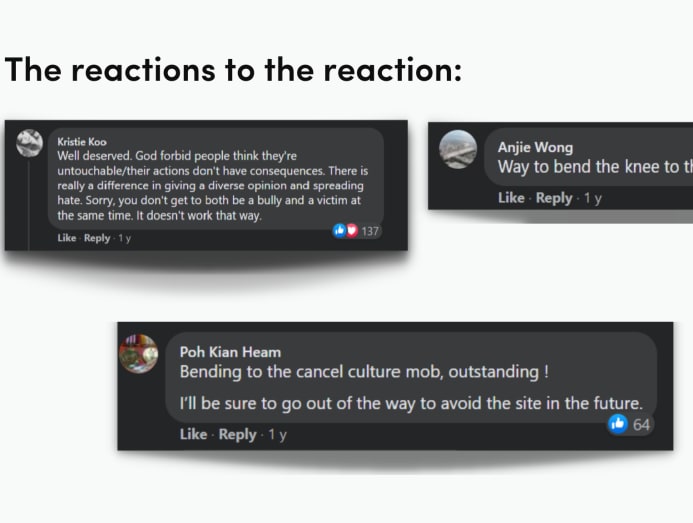

When Ms Cheng was dropped from a show she had been slated to host on Clicknetwork as a result, Clicknetwork’s Facebook statement drew polarising views. Some commenters supported the move against “racism, bigotry and hate”, others expressed disappointment that a long-standing relationship could be discarded so easily.

Certain topics also tend to result in greater polarisation, such as politics, race and even lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) issues, noted Prof Lim.

“Essentially, communities that have been marginalised, that have felt that they are less than fairly represented by the mainstream media, would seek alternative platforms to project their views. And that's when the complications of the public space will result in different kinds of viewpoints being aired,” she said.

“Moderation seems so hard to find on both sides,” shared Facebook user Gary Yeo over the phone with CNA.

The 43-year-old, who considers himself more pro-establishment, noted “some common areas” between groups on both ends of the spectrum. People typically share opinions in a closed environment and both sides are echo chambers, with similar viewpoints being made.

However, irrespective of whether he has articulated opinions which might be seen as pro- or anti-establishment, the online reaction has often been emotional.

“I used to think the opposition had a lot of anger. Essentially when you disagree with them, they will shut you down and try to silence you. And I thought the pro-establishment side was better. Like maybe they’re less harsh and use less insults,” he said.

“But when I once disagreed with the Government’s views - for example, when I felt that ‘race’ should be taken out of the NRIC - (someone in the pro-establishment group) tried to silence me, even though it was just a minor disagreement.”

But similar attacks were thrown at Mr Yeo when he sided with pro-establishment perspectives. Some opposition supporters would “outright argue or insult” him. They have also suggested he is a member of what has been described as the People’s Action Party’s Internet Brigade (PAP IB), a group of people believed by some to be ready to jump online to fight the ruling party’s corner.

“Saying ‘PAP IB’ is the most common and fastest insult. The moment you disagree, you become a PAP IB. I mean, I'm not even a PAP member or involved in grassroots. They also insult you by calling you stupid,” he said.

And polarising views aren’t just hurled across the aisle. In-fighting also occurs among people supposedly from the same camp.

“It’s not so much ‘in-fighting’ as it is just different opinions being put on the table. That’s just an inevitable consequence of the fact that, regardless of which side of the political spectrum you’re on, there’s bound to be disagreements on the specificities of certain socio-political issues,” explained Mr Paul Jerusalem, a 27-year-old researcher pursuing a masters in communication and new media at a local university.

Sometimes, this friction might be due to “identity politics”, he added.

Mr Jerusalem, who is a known social media figure among the younger "left-leaning" online crowd, recounted an incident where a Singaporean mainstream media journalist “momentarily fell out of favour” with some people on Twitter. She had expressed a view that, while not in opposition to theirs, was misconstrued as such, even though her old tweets would have suggested she held “similar political sympathies” to them.

“I think the fact that she has (her publication’s name) on her handle leads people to make certain assumptions about her, in addition to other visible identity markers such as race,” said Mr Jerusalem, whose research areas of interest include online discourse and cultural studies.

Making snap judgments out of convenience about someone’s position on an issue by looking at visible identity markers, such as their gender, age or race, is part of identity politics, he explained.

“When people talk about identity politics, a lot of it is fear mongering and bogeyman politics. But I think there are instances where assumptions are made based on apparent indicators of your positionality; not everyone is going to dig into the history of what you’ve said and come to nuanced conclusions on where you stand,” he added.

ONLINE SLANG: HELP OR HINDRANCE?

Any social media user knows snap judgements are often effectively expressed through online slang, but language can also hinder communication.

“Language, including slang and colloquial terms, add to discrimination and polarising views. But this is neither new nor precisely a social media phenomenon,” observed Assistant Professor Saifuddin Ahmed from Nanyang Technological University’s Wee Kim Wee School of Information and Communication.

He added that slang can signal “alienation”, implying one group is more “in the know” than others, which can worsen social relations between groups.

What social media does, he noted, is broadcast such language to a broader audience, “aggravating the alienation of out-group members”.

Moreover, different groups of people might have different assumptions around a particular term, leading to misunderstanding, said Prof Lim.

“A lot of the very fraught arguments can sometimes be triggered by a particular term being used with one intent but being interpreted with an alternative intent.”

Prof Lim pointed to the PA standee mishap as an example where different groups didn’t share the same understanding of racism.

Where slang is concerned, labels like "snowflake" and "boomer" tend to also be commonly expressed in polarising views.

"Snowflake" usually implies an overly sensitive or easily offended person, who believes they are entitled to special treatment, while "boomer" is used to dismiss someone who has out-of-touch or close-minded opinions. "Snowflake" is associated with younger generations, while "boomer" is commonly tagged onto older generations.

“People want to express themselves with impact. They want to be seen as witty and clever. When they use these labels, there is that sense of wanting to project that you're always with it, that you know what sort of urban slang is in vogue now. Plus, social media exchanges are snappier and more succinct,” explained Prof Lim.

“But such terms can be harmful in the sense that ... you can find them becoming sort of lightning rods for debate, the way it was with the whole ‘snowflake’ comment.”

Using these terms to evoke humour and not nuance is par for the course these days, noted Mr Jerusalem.

“With online discourse, certain turns of phrase are incentivised. Things like ‘clapping back’ without much nuance, and doing so to evoke humour and not nuance, is commonly perceived as perfectly fine, because not everyone is trying to write an essay online,” he added.

“I think there’s an element of humour on social media. Sometimes we say things just to be funny. It’s one of the key gratifications on social media, where we seek levity and laughter. Like if I’m going to engage in this, I might as well have fun.”

Sometimes, however, the phrasing “might not be so attentive to how it can potentially have an impact on the real human being on the other side of the screen”, he said.

“It can be very easy to engage in a way that’s all-or-nothing, black-or-white, if not plain combative.”

TROLLING: WHERE TO DRAW THE LINE?

So when it seems so simple to slide into extremes, where does one draw the line between useful and unhelpful comments, irreverent comebacks and harmful trolling?

For Mr Jerusalem, the basic concept of trolling might not even have a definition everyone agrees on, although he pointed out that most people would agree that trolls are “fake profiles” or “people who engage in bad faith arguments”.

But he suggested that trolling isn’t limited to a standard idea of trolls, and that many people involved in online discourse actually engage in some kind of “troll-ish behaviour”.

“It’s adopting a tonality that’s frivolous and un-serious, often incorporating some extent of irony,” he explained.

Facebook user Michael Lum, 49, told CNA that he has been on the receiving end of trolling and personal attacks.

He said he has become used to being called “boomer” by younger people who hold extreme views that go against his support for certain government policies. Some have gone as far as commenting on his white hair, calling him mad or an idiot.

“For many people my age, and even those around 35 to 40, if they have a beef with the Government, that’s fine. They would’ve been victims or benefactors of policies,” he said.

“But those in their 20s, or 18-, 19-year-olds, who have views that are so extreme, like the Government is bad, the Government is making my life miserable, my thought is that you were born into a situation from day one. The situation didn’t occur while you were trying to have a life. So for them to hate the Government, I can’t really see the rationale.”

Anonymity, or at least a sense of being anonymous, fuels trolling, experts agreed.

“Our online presence is often an extension of ourselves, but anonymity and less accountability on social media allow for more toxicity and greater polarisation, which may not always happen in offline settings,” said Prof Saifuddin.

“There is something called the online disinhibition effect,” added Prof Lim.

“That visual anonymity, that lack of identification, as well as the absence of social cues from synchronous communication can lead us to become very deceptive and say very extreme, obnoxious expressions that we might not say in a different situation.”

Prof Lim recalled Gamergate, where female gamers were “very vociferous” about women’s rights in games. What was interesting, she noted, was that many of the gamers who retaliated against these women with vicious and violent threats were found to be teenage boys, who found a convenient platform to propagate views that they would otherwise not share.

That said, on rare occasions, trolling can be used to “defend yourself from attacks”, especially if you’re “a minority in any sense”, shared Twitter user Madhu Vijayakumar.

“Often growing up, you had to learn how to defend yourself from discriminatory attacks. You’d learn the hard way that sometimes coming in good faith… people would just use it as a way against you or make fun of you. The ‘survivability’ is also just about making clapbacks.”

While trolling isn’t the same as being vocal or standing up for oneself, the line can sometimes blur.

“Minorities have become more vocal than before as the rise in public racist incidents has triggered a trauma expulsion,” the 22-year-old suggested.

“In the context of race, what we’re seeing is a lot of expulsion of trauma from minorities. To a point where they might not be saying things that are nuanced, but they are doing this because nobody has ever listened to their concerns before. And now that everything’s in the open, suddenly the gates have opened.”

Ms Vijayakumar herself is an example. About two years ago, she started becoming more vocal on Twitter, as it helped her to become more empowered and vocal about her experiences. However, she felt that she had “no restraint”, and would “say anything and everything because it was an expulsion” of all her experiences that she felt she’d kept in.

But when being completely honest about one’s position could attract even more trolling or criticism, some social media users choose to filter their words. For instance, Ms Vijayakumar doesn’t consider herself anti-establishment, yet she doesn’t feel like she can be open about it on "left-wing" Twitter, where she’s an active participant.

“I do think I conceal sometimes, like I have to filter my words a bit. … Nuance is what polarisation lacks,” she said.

Ultimately, regardless of what drives online polarisation, MP Leon Perera (WP-Aljunied) told CNA that a danger is people becoming “incapable of having a reasonable discourse”.

“Our public figures and role models in society need to model that behaviour, and say, hey we can have a civil conversation across different points of view. We can agree to disagree and we don't have to persuade each other and that's fine. There’s no shame in that,” he said.

“It doesn't mean that every conversation has to lead to an outcome where one person's view prevails, because that's the correct view. I think this is a big problem in Singapore.”

WHO’S RESPONSIBLE FOR CIVIL DISCOURSE?

The YouGov survey found that while 65 per cent of respondents think people with vastly different views can engage in civil and polite conversation online, only 53 per cent of respondents had actually seen it happen.

This desire for balanced views online isn’t new, but it’s hard to achieve, observed the individuals CNA spoke to, from experts to the average social media user. Different people also have different ideas of how they define balance, with their personal bias possibly enabling echo chambers.

Take Mr Yeo, who once received disparaging remarks from both pro-establishment and anti-establishment camps online. He’s a follower of Facebook page Critical Spectator, which has been painted with the same pro-establishment brushstroke as Calvin Cheng and Wendy Cheng. The page, run by Polish national Michael Petraeus, typically features commentaries on local issues.

Mr Yeo calls his takes “refreshing” and “quite different”, explaining that he “dares to say things that might be more controversial”. He cited a post where Critical Spectator had looked at the COVID-19 outbreak at Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

“There was some panic, and things seemed bad. But he put things into perspective, relating the numbers to the whole world. We’re quite a low-risk country, with low infection rate and high vaccination rate,” he said.

While Critical Spectator’s fans applaud his writing, he has also attracted criticism. Sometimes, this has resulted in online spats emerging where the language used has reflected some of the trends observed in the YouGov survey.

For instance, in June this year, local playwright Alfian Sa’at wrote a Facebook post to say “a certain Polish polariser” was “decontextualising and distorting” things he had written on social media to do a “takedown”. He called this “pathological behaviour”.

A few days later, Mr Petraeus addressed Mr Sa’at’s post with another Facebook post: “Never a dull day with left-wingers!” he wrote, saying that Mr Sa’at’s actions made him look like a “gigantic hypocritical snowflake”.

Shortly after, local publisher of former socio-political site The Middle Ground, Daniel Yap, came under fire on Critical Spectator. Screenshots on Critical Spectator showed that Mr Yap discovered Mr Petraeus’ name was Michał Piotr Pietrusinski, and left a Facebook comment asking The Online Citizen’s editor to amend his name in articles “for Google to crawl properly and index”.

In a Facebook post on Critical Spectator addressing this, Mr Petraeus wrote that he was giving space to these “loonies”, in order to “expose all of the self-professed fighters for better Singapore for the hateful frauds they really are”.

Mr Jerusalem said that it would be “quite a big charge” to hold particular individuals as a source for the trend of online polarisation.

“My sense is that with or without these individuals, there’d still be a diversity of views and the factions that currently exist. People sometimes find it convenient to reduce the views of these factions down to an identifiable figure that represents them. But I think regardless of that, there’d still be polarisation,” he said.

“The presence of individuals with strong views is not the only reason for polarisation. There’s also echo chambers and bubbles that exist within each platform, and a lack of spaces where people can engage in intergroup dialogue, whether online or in person.”

He added that Singapore has its own unique challenges in terms of political participation.

“Many people regard society as not being very hospitable to that, so this discourse is taken online.”

On the other hand, Ms Tin turned to a line from Spider-Man to describe her take on these high-profile individuals: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

“If you’re a public figure, and if you have a significant following, you know you have an influence over people, then I think your response also needs to exercise greater care and responsibility. Who can be 100 per cent sure that you’re always right?” she advised.

“I would prefer that even as you state your position, (you observe) the tone with which it’s said. It’s about being responsible for how you ask a question because it affects other people’s opinions, being cognisant of our impact on others. As much as we want people to listen to us, we must also be willing to listen to others.”

Beyond what the Government can do, Ms Tin said society has a “powerful” role to play.

“We’re powerful on our own. Whatever’s being talked about online is done by people themselves. So if you’re able to recognise wrong-doers and the harm they’re inflicting on other people, you can rally people to come in and say, no, this is wrong, bullying is wrong,” she said.

“Even if that individual can’t be banned from Facebook, if there are enough people willing to stand up, I think it will help to balance the sentiment and help the victim to feel like they're not alone.”

If that fails, social media companies like Facebook have hate speech policies that could help.

Facebook defines attacks as violent or dehumanising speech, harmful stereotypes, statements of inferiority, expressions of contempt, disgust or dismissal, cursing, and calls for exclusion or segregation, Ms Kate Blashki from Facebook’s Content Policy team told CNA.

Ms Blashki added that Facebook prohibits attacks on people based on their “protected characteristics”. This is defined as their race, ethnicity, national origin, disability, religious affliation, caste, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity and serious disease.

For content that doesn’t violate hate speech policies, she noted that they may violate other community standards, like those related to bullying and harassment.

“However, we know that the same words can be considered a slur in one country and totally benign in another, and that changes in language can occur quickly. We’re constantly working to understand these cultural and linguistic nuances,” she added.

But such extreme measures might not be necessary, said Workers' Party's Mr Perera, who said another danger he sees is political apathy.

He observed that away from online echo chambers, many people in Singapore “aren’t interested in politics”, unless something affects them personally.

“They don’t have a view about what an ideal society should be. I think that is profoundly dangerous, and I see that the biggest danger of Singapore is that people are more focused on personal interests,” he said.

“I’ve seen people who profoundly disagree on certain policies, and their response is that they’re going to migrate. Why isn’t your response that you’re going to stay here, and fight for things to change? Maybe it’s just that we’ve been entrenched in a one-party dominant political system for so long, that people just can’t see how that can change through citizen action.”

FIGHTING ONLINE POLARISATION THROUGH INDIVIDUAL ACTION

The individuals CNA spoke to agreed that the responsibility to create more civil discourse boils down to their own actions - whether that’s disengaging with people who just want to argue or learning to express their views in better ways.

“We do have a responsibility (to build civil discourse), but sometimes it’s also about making yourself heard in a way that you need to be heard. That doesn’t mean directing hate to people, but you also don’t owe anyone kindness or civility,” said Twitter user Ms Vijayakumar.

“If someone says something very offensive, you’re allowed to be offended. You cannot conceal your humanity just to make online discourse a bit better.”

If you think social media is polarising, don’t assign too much power to it, she added.

“Social media pushes for action in Singapore, as (some might feel that) avenues for action are few and concerns are given little importance, unless a big storm is made on social media. It’s good for this purpose, but there are downsides such as lack of nuance, bullying, doxxing and exhaustion. So I would say pick your battles.”

Looking beyond social media polarisation can simply mean opening yourself up to “a diversity of views”, which is healthy, advised SUTD's Prof Lim.

“That to me is the first step towards healthy discourse, because if you don't know what the other camp is thinking, and you don’t actually understand why they think the way that they do, how can you even begin to come to the table?”