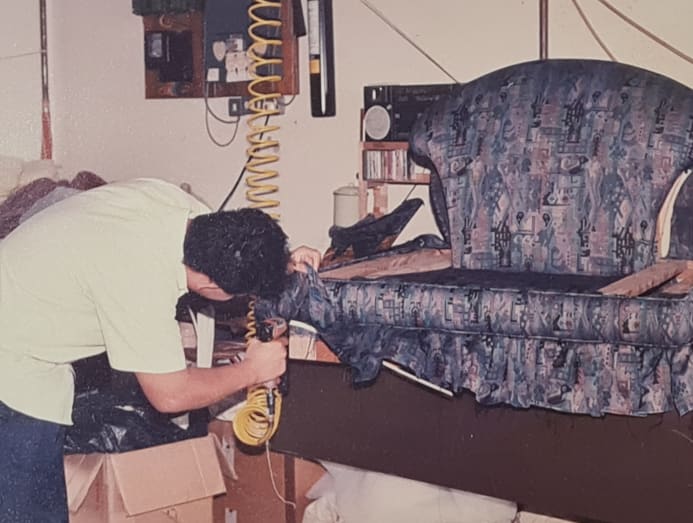

How this third-gen custom furniture maker pulled his family business, Danovel, out of a 10-year rut

Marcus Wong banked on technology to modernise Danovel.

Marcus Wong, business development director of Danovel, a company that specialises in handcrafted bespoke furniture and upholstery. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

There aren’t many mod cons that capture a zeitgeist quite like the sofa — ubiquitous enough to bleed into the background of a domestic diorama, yet distinctive as a marker of shifting trends.

Consider it as a centrepiece of popular culture: Characters from sitcom Friends perpetually coiled around a chintzy, dimpled orange mohair settee like vines, blithely bandying about their first-world grouses over oversized coffee mugs. It’s also employed as a literary device. In F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, dissolute socialite Daisy Buchanan and her friend are described as being buoyed on a sumptuous couch “as though upon an anchored balloon,” symbolising their carefree but ultimately vacuous existence.

It isn’t really that profound for third-generation sofa specialist Marcus Wong. While his family’s bespoke furniture firm Danovel may major in plush upholstery catering to all manner of sybaritic whims, he sees the couch as a repository of memories rather than status symbol. Sprawled in their living room is a four-seater sectional sofa that has been re-upholstered multiple times over the course of three decades and is inextricably seamed with his childhood.

“It’s where I faked sleep so that my parents would carry me to my bedroom, and where we did our homework as kids,” recalled Wong. His heirloom may not be the most extravagant, but to him, old is gold. “A well-made piece of furniture is one that you can pass on to generations; not everything is made to be thrown away,” asserted the 42-year-old.

CHASING THE SINGAPORE DREAM

Longevity is a running theme in our conversation, which traced Danovel’s heritage as a realisation of the ‘Nanyang dream’. In the 1960s, immigrants such as skilled labourer Koh Khee Khim converged at Singapore’s shores on a wing and a prayer, to pursue economic opportunities beyond the grip of China’s tumultuous Cultural Revolution. A Shantou native, Wong’s maternal grandfather fell into furniture-making by chance, which paid off during Singapore’s meteoric nation-building epoch.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, people moved from informal settlements to HDB flats and that’s where the furniture industry grew,” explained Wong. Over the succeeding decades, the outfit — incepted as Hock Hin Company — evolved from producing spare wooden frames that cradled boxy cushions, to plush pieces upholstered in multifarious imported materials. This tony new direction can be credited to Wong’s mother, Koh Siag Lan, who acquired franchisee rights to South African home decor retailer Biggie Best and opened an outlet at Tanglin Shopping Centre in 1996. The since-shuttered store was largely patronised by expatriates whom Wong describes as discerning aesthetes.

“Singapore opened up to the world in the 90s, when many MNCs came. With the influx of talents and cultures, we were exposed to more high-end furnishings,” recounted Wong. Amid this bonanza, his uncle — the first of the second-generation siblings to join the family business — branched out towards an entirely different market, mass-producing furniture in Taiwan. His company owns the patent to the iconic Prima Bonn bench rigged with polypropylene shell seats — a fixture of waiting rooms the globe over.

The 60-year-old Danovel, for all intents and purposes, is a “made in Singapore” brand, and it wears its appellation with pride. Everything from carpentry to upholstery takes place in their factory in Ubi, which customers are welcome to visit if they want to burrow into the furniture crafting process. But why the dogged insistence on maintaining a facility in a country where land is priced at an eye-watering premium?

“If the Italians can manufacture in such an expensive and culturally refined country, why can’t we do it in Singapore as well?” mused Wong.

Against the ruck of ersatz Scandi chairs and tables flogged on platforms such as Taobao at alarming speed, Danovel has quietly whittled out its niche in customisation. Among its more outre commissions, is a 90-degree straight-backed sofa for a chiropractor, as well as one comprised of natural materials — from cotton fabric covers to natural latex stuffing.

As you might imagine, pandering to that level of personalisation does not lend well to a roaring trade. That’s not to say the firm wasn’t raking in a tidy profit when Wong quit his job in Certis Cisco’s quality management department in 2008 to assume the mantle of business development director. The computer science graduate admits that he decided to help run the business out of a sense of obligation but grew to appreciate the fine points of furniture crafting.

He jump-started the traditional company’s digitalisation journey by introducing an internal database detailing specifications of all its past projects to improve quality control. He also developed its website, at a time where furniture retailers had yet to cotton on to e-commerce. Obtaining the buy-in of his senior craftsmen wasn’t cut-and-dry. The soft-spoken young successor says he had to “be the first one in and the last one out” of the factory to earn their respect through his own merits.

“You have to crack your brains to encourage them to try different solutions. That’s when they start to believe it can be done,” he asserted.

TRANSLATING RISK INTO REWARD

While this was taking place, a bruising Global Financial Crisis shuddered across multiple sectors, felling goliaths in banking and beyond. Predictably, Danovel’s sales took a nosedive. What followed was a protracted dry spell. The company was in the red for the better part of a decade, during which Wong borrowed from friends and relatives to staunch their cash flow issues.

“I even went door-to-door around Bukit Timah distributing flyers, often facing barking dogs at GCBs (Good Class Bungalows),” recalled Wong. To cut their losses, he shuttered their flagship factory in Eunos. Yet, folding the firm was never in the cards. “Our commitment to the business went beyond financial concerns, it was about preserving my grandparents’ legacy,” stressed Wong.

Neither was leaving the business moribund. In fact, you could say the unfavourable circumstances warranted bold moves. While slogging to eke out sales, Wong invested in technology such as five-axis and laser machines, with the support of government grants. His latest acquisition is a pair of robotic arms for enabling greater precision.

“These technologies not only prepare us for the workforce of the future but also help us to improve our craftmanship,” explained Wong.

Perhaps the closest to the wind he’s flown is by ploughing over a million dollars into Danovel’s showroom at Pasir Panjang. “Convincing my parents wasn’t easy as we are quite a conservative family, and mortgaging our own house to invest in this place was a huge decision to make,” revealed the reserved entrepreneur.

It may be premature to determine whether the risk has paid off, but Wong is convinced that owning their premises “shows customers that we are not a fly-by-night company.” What he can aver with a degree of certainty, however, is the effectiveness of technology in filliping productivity. This was especially advantageous in 2018, when the company hit a stride with its B2B arm, having secured a plum contract with Resorts World Sentosa. It wasn’t so much of a deus ex machina moment, than the result of years of pegging away at a steady catalogue of smaller projects. Today, Danovel counts Starbucks, Accor and Pullman Hotels and Resorts among its big-name clients. It also customises furnishings for luxury yacht maker Grand Banks Yachts.

Wong is pleased to report that the company’s accounts have finally been tilted into a positive balance. With its financial woes in the rearview mirror, the third-generation owner shared that he’s looking towards succession planning beyond kin. Though he heads the company together with his mother and Nepal-based sister, he says they’re focused on nurturing long-serving employees for leadership roles. He’s confident that cultivating Danovel as a custom furniture-maker par excellence can ensure its sustainability, as opposed to feverish expansion.

It's a cautious outlook typically associated with his home country, whose overriding qualities include financial prudence and stoicism. In many respects, you could argue that Danovel’s journey closely follows the contours of the Singapore story, ebbing and flowing to its changing fortunes.

What then, distinguishes a “made in Singapore” brand?

“Profit is one thing, but we still want to ensure that the customer gets the best value and quality in everything we do,” concluded Wong.