Collecting Iskandar Jalil ceramics in Singapore: ‘You don’t just buy one’

With about 100 works from celebrated potter Iskandar Jalil in his collection, Dennis Tan’s pursuit of pots has gone from hobby to heritage preservation.

Collector Dennis Tan at home with a selection of Iskandar Jalil ceramics from his private collection. (Photo: CNA/Kelvin Chia)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Cultural Medallion recipient Iskandar Jalil needs no introduction. A living legend, the 85-year-old master potter, sculptor, designer and educator is a favourite among art lovers.

Think of him as the poster boy for the IYKYK collecting crowd: everyone from architects and academics to civil servants, diplomats and old-money families – the kind of people who don’t need to post their shelfies on Instagram.

They do, however, fawn – no, obsess – over his sculptural vessels, lighting, furniture and other objets d’art. His pieces aren’t ostentatious, but they leave a lasting impression. They feel almost meditative, demanding that you slow down and absorb the artistry before you.

One such admirer is Dennis Tan, 57, the regional CEO of a global life insurance company who has amassed “at least 100” of Iskandar’s works. Most of them reside in his home – a three-storey bungalow in western Singapore – which he shares with his wife and three grown-up daughters.

“You don’t just buy one,” is a common refrain among Iskandar’s fervent fanbase. The first piece, they say, is usually acquired out of aesthetic appreciation. The second – and subsequent pieces – rapidly spiral into obsession.

Apparently, the longer one lives with them, the more one notices the quiet authority they command in a room: the way the pieces are weighted and balanced, or the way they catch the light at different times of day. Many collectors start with a single vessel and end up assembling clusters – shelves, corners, even entire rooms – anchored by Iskandar’s ceramics.

That’s certainly true of Tan, whose dining room is presided over by a bespoke bookcase filled almost entirely with Jalil’s signature earthy, rough-hewn teapots, teacups and vases. What strikes you is the potter’s prolific range: no two pieces are quite alike, whether in shape, scale or expression.

“In my previous home, every corridor and staircase was filled with pottery. My family pleaded with me, ‘Please, enough!’” Tan recounted with a laugh.

To be fair, Tan’s collection extends beyond Iskandar’s ceramics. He’s an ardent aficionado of vintage Danish furniture, as well as Singaporean and Southeast Asian art. These are spread throughout the house, forming a backdrop to the family’s everyday life.

The entire home seems to heave with art, reflecting decades of collecting. Tan points out works by cultural heavyweights like Brother Joseph McNally, founder of LASALLE College of the Arts; oil painter Chua Mia Tee; Malaysian batik artist Dato’ Chuah Thean Teng; and sculptor Ng Eng Teng.

It isn’t just historically significant artists that Tan accumulates; he’s also plugged into the zeitgeist. “This entire wall – and that one as well,” he gestured, “will showcase this young Singaporean artist I’m fiercely supporting, Yeo Tze Yang. I’m a proud Singaporean, and very protective of our culture and history. And I think it’s important that we do so.”

AN INTENTIONAL APPROACH TO COLLECTING

Many collectors view owning an Iskandar Jalil as owning a piece of Singapore’s intellectual and cultural fabric. For them, Jalil’s work is the antithesis of the shiny, iconic image of Singapore – the futuristic urban cityscape that occasionally features in Hollywood productions. Instead, Jalil’s oeuvre speaks to the country’s thoughtful, disciplined, creative side: deeply rooted, yet open to the world – traits that underpin its progress.

“When you look at places like Indonesia or mainland China, you really see a vibrant local art scene,” Tan said. “In Singapore, though, we’ve historically been very focused on the basics – economics, science, practicality. Creativity wasn’t always prioritised.

“That’s why artists here – whether ceramicists or painters – are actually quite remarkable. To persevere and produce meaningful work in that environment is no small feat.

“And as Singapore developed, our priorities shifted even more towards financial and economic gains. The reality is, if you choose to be an artist today, you’re probably not going to make a great living. You’re certainly not going to get rich.”

Over the past decade, as Tan became more intentional about collecting, his focus sharpened. What began as an interest in paintings and ceramics evolved into a clear commitment to Singaporean art. For him, collecting is not about accumulation or prestige, but purpose. “I really want to do whatever I can to help support, protect and preserve our heritage.”

That philosophy also shapes how he collects. He is emphatic that he has never sold a single piece from his collection, nor does he intend to. “I collect because I want to preserve it, because I enjoy it, and because I want people to enjoy it,” he explained.

While he respects other collecting approaches, his own position is firm: “I’m definitely not one who buys and sells. I don’t trade. I’m here to really collect, and hopefully pass it on to the next generation,” he added, referring to his three daughters, who are 26, 24 and 19.

HOW IT ALL COMES TOGETHER

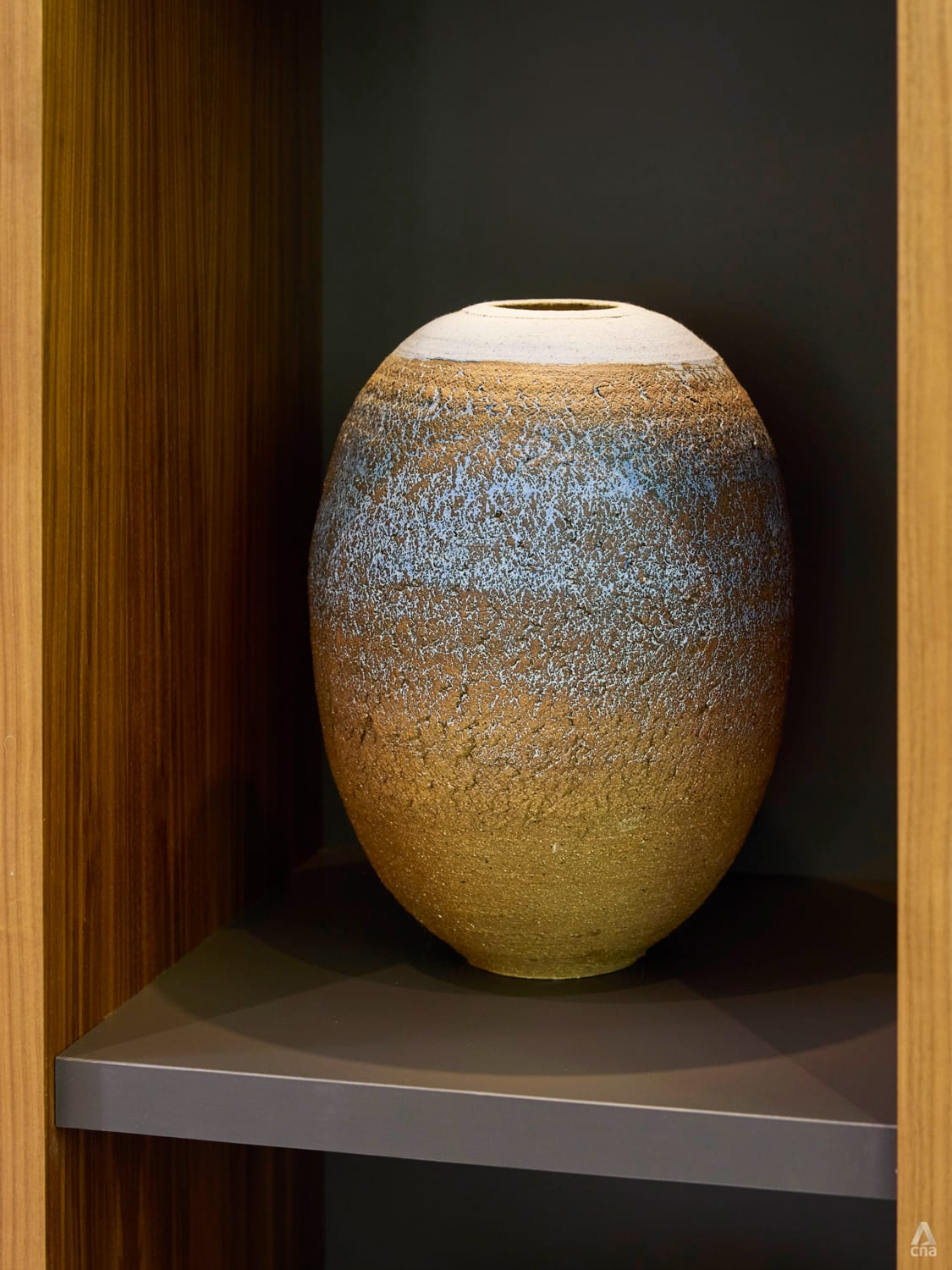

Iskandar’s ceramics are both functional and aesthetic. With clay as his primary medium, one of his fundamental philosophies is to shape everyday objects into objects of desire, with a sensitivity to material and a monk-like level of restraint.

Another keystone credo is the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, where accidental marks and asymmetries are embraced as poetic rather than rejected as flaws (Iskandar studied ceramics in Japan in the early 1970s).

His teapots and other serving vessels often pair rugged, expressive ceramic bodies with natural wooden handles fashioned from twigs or branches – a design language that speaks to tactility, a connection to nature, and wabi-sabi.

It’s this quiet complexity that allows Iskandar’s pieces to exist effortlessly in different environments. They look completely at home beside modernist furniture, Southeast Asian sculptures, or contemporary design.

In Tan’s home, this quality is used to the best effect. The living and dining rooms juxtapose all three of his major collecting genres – Southeast Asian paintings, vintage Danish furnishings and Iskandar’s works – with remarkable ease.

“Full credit goes to my wife,” Tan admitted with a laugh. “She’s the one with the eye to put things together. For me, my passion is just collecting!”

‘COLLECTING IS ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS’

The family moved into the property in early 2024. It fit their needs – a place where they felt they could retire comfortably. Keeping the main structure intact, the only remodelling was to the interiors, especially on the first floor.

Wanting more natural light to flood the space, the couple demolished partition walls and replaced exterior walls with floor-to-ceiling windows. The result is a large, open-plan living, dining and kitchen area that allows the various collections to “breathe”.

A few years after he started collecting vintage Danish furniture, Tan’s attention turned to Iskandar Jalil. “The frustrating thing is that you rarely see his pieces in circulation. You might find one or two in museums, but when you go to galleries, there’s very little available – simply because people who own his works don’t want to sell.

“So once in a long while, when a small piece came up, I would grab it. Back then, it might have cost S$2,000 (US$1,555) or S$3,000, and that’s how I began. Over time, the collection grew. A lot of what I’ve collected is his earlier works. They’re big and heavy, and because Iskandar is older and frailer these days, he can no longer make pieces like that.

“In recent years, what he’s been able to produce is much smaller, which is typical for artists working with clay. So whenever I came across these large, substantial works, I made sure to secure them. I’m very grateful to have encountered these pieces. Some were previously held by government agencies, and years ago, when a batch was released – perhaps due to renovations or restructuring – I was able to acquire some of them.”

Ultimately, Tan noted that collecting is about relationships. “When you build trust with gallery owners, they’re the ones who know where the works are and who has what. They’ll source pieces for you when they become available. The other route is auctions – but there, you have to be disciplined. If the price goes too crazy, you learn to say no and let it go.”

GOING AGAINST THE GRAIN

As Tan pored over his collection, one piece jumped out: a voluptuous receptacle with three handles and a spout, notable for its striking crimson glaze.

“This one is very special, because you very rarely get red,” Tan explained. Achieving that colour is not merely aesthetic but technical – even risky. “It’s not just the colour. To get that red, the materials can be more dangerous, sometimes even slightly toxic. That’s why you don’t see many of them.”

By contrast, Iskandar is best known for what he calls Iskandar Blue – a signature hue that has become synonymous with his name. “I like the blue,” the collector added. “I like his earthy tones.” In all these pieces, whether red- or blue-tinged, Iskandar’s mastery of glazing is unmistakable.

Part of what draws Tan to Iskandar’s work is the way nature is folded into the making. “Many of his pieces have these elements,” he said, pointing to the wood accents. Iskandar is known to collect driftwood wherever he goes – beaches, forests, especially in Japan – drying and storing it until inspiration strikes.

“Each time he makes something, if a certain piece fits the look and feel, he’ll use it.” The result is a body of work that feels endlessly varied.