These Asian designers are redefining what materials, beauty and sustainability mean

Across Asia, a new generation of designers is challenging ideas of beauty, value, and waste — transforming everyday materials into objects that reflect care, culture, and consciousness.

Across Asia, young designers are reimagining discarded materials into objects that challenge how we define value, craft, and responsibility. (Photos: Courtesy of respective designers; Art: CNA/Chern Ling)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Across Asia, a new generation of designers is rethinking what materials, beauty, and sustainability mean. At this year’s EMERGE (part of FIND – Design Fair Asia), young talents from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and beyond showcased works that blur the lines between art, craft, and design — transforming waste into wonder, heritage into innovation, and the everyday into the extraordinary. From discarded plastics and factory offcuts to glass, coffee grounds, and even cow dung, these creators are redefining how we relate to the objects that surround us. Their practices tell stories not just of form and function, but of renewal, identity, and resilience — each offering a glimpse into the evolving narrative of contemporary Asian design.

IVAN HO, TIZUMUKA

Piles of offcuts at factories; plastic pieces on the beach; fabric trash in studios. These are some examples of what inspires Singaporean designer Ivan Ho. Using them, he creates objects such as furniture and vessels. “Design should not only create beauty or function, but tell stories – about extraction, consumption, waste, renewal,” he explained.

Perfectly embodying this is Parasitic Edition 2, made up of an armchair and stool, that he showed at EMERGE. Echoing forms of classical Chinese furniture, he describes them as “survivors of transformation”. Both are made from marginal materials: HDPE granules most commonly from post-consumer plastic waste, repurposed polyester fibres and offcuts.

Painted in black, they come across as raw and austere in a bid not to distract from their textured, uneven form that Ho hopes will invite repose and reflection. “I wanted to create a counter-narrative: that the discarded can support us, hold us, become home,” he said.

He believes that design is a dialogue and has a three-pronged philosophy. The first, “material empathy”, means listening to where they came from and honouring their history. In his hands, they undergo “transformative reuse” by being given a new life and challenging the linear lifecycle of consumption. Finally, the outcome must invite questioning, reflection and exchange.

Happy with his current direction, Ho intends to delve deeper into exploring material waste, “I want to discover new ways of coaxing beauty and meaning from what we cast aside, to continue challenging the boundaries of what can be considered precious.”

MAY MASUTANI

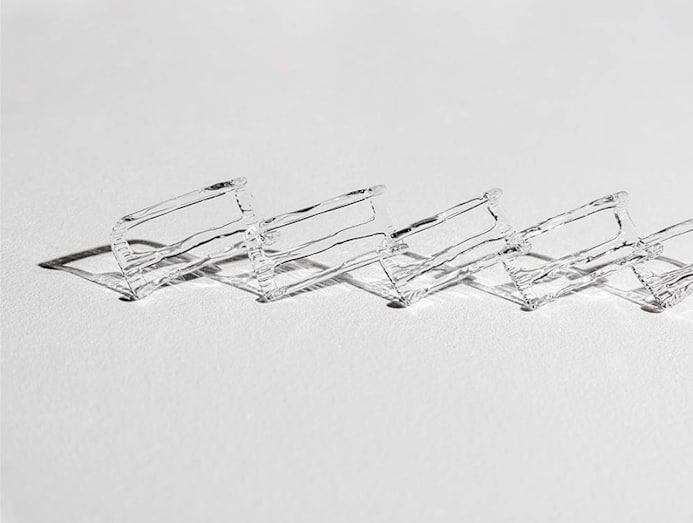

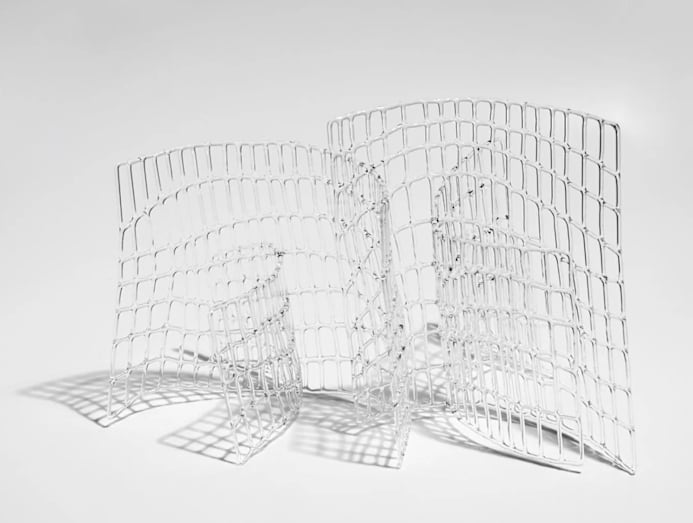

More artist than designer, the works by Singaporean May Masutani are captivating for their delicate, ephemeral quality. At EMERGE, her piece, Gather, dangled down from the ceiling, appearing to be made up of individual links, but was, in fact, crafted entirely from clear borosilicate glass.

“The form is reminiscent of kusari-doi or rain chains, a traditional architectural feature in Japanese temples and gardens used to channel rainwater from the roof to the ground. Similar to cascading rainwater, Gather depicts flow and movement,” she explained.

The rest of Masutani’s portfolio is equally exquisite, where she has the remarkable ability to mould the material using a technique called flameworking to resemble the finest lace. “I am often inspired by the patterns I find in nature and my surroundings,” she revealed.

Said surroundings are in Toyama, Japan, where she lives, after she graduated from its eponymous institute of glass art in 2020. The city is also known for its World Heritage Gokayama villages and Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route that meanders through scenic forests and waterways.

No surprise then that she takes much of her cues from what is around her. “I like to observe things in my surrounding environment; it helps me be present when I notice the slightest things,” she said. “It is a similar feeling that I try to represent in my work.”

ERIC TIAU, BIG HAND CREATION

If you look at Eric Tiau’s work and start smiling, he would have reached his goal. “I believe design is a process of creating happiness and uplifting those around us,” said the Malaysian designer.

His cheerful BEORI REST+ lamp collection, presented at EMERGE, certainly turned heads – firstly for their bright colours (in pink, yellow and green) and then for their unusual shape. Aesthetics aside, joy is also evoked with the realisation that it is made from rejected medical gloves, blended with biodegradable PLA derived from fermented plant starches.

There is more. It is made using a “Snap & Built” mechanism, without screws or adhesives. This means assembly, dismantling and maintenance is easy, while keeping long-term repair, reuse and recycling in mind.

For Tiau, sustainability practices ought to be second nature. “We set out to design something simple and beautiful that first delivers values in balancing lifestyle and resting wellness, then only does it lead to conversations about sustainable values,” he explained.

Plans are under way to make the collection available in major Southeast Asian cities soon, with the possibility of collaborating with local designers to give each lamp a signature cultural voice and identity.

Tiau said: “We want it to be a lifestyle marker – a companion lamp that contributes to the golden hour before sleep: to pause, relax, be present, and reclaim your own me or we-time in today’s busy world.”

ADHI NUGRAHA, COWKA

With their rounded forms and lively colours, the last thing you would expect is that the works by Indonesian designer Adhi Nugraha of Cowka are made from cow dung. Don’t turn your nose up at it though (no, it doesn’t smell bad either), since it’s for a good cause.

Their improper disposal by dairy farmers in West Bandung has led to landfill and water pollution. Nugraha therefore saw an opportunity to mould them into lifestyle items, such as speakers, lamps and table clocks.

“We collaborate with local people, predominantly women, and transform a local resource into our products. We rely on simple, appropriate technology that is a perfect fit for the area,” he explained.

A believer that design is a problem-solving endeavour, Nugraha couples his approach with a sense of responsibility and playfulness. He has also collaborated with Japanese design strategist Eisuke Tachikawa to create biodegradable, acorn-shaped products.

More plans are in the pipeline to maximise the potential of this unique material. “Our current projects involve creating a range of interior elements, such as tiles, ceiling panels, and wall decor. I am also very excited to explore the application of this material in a wide range of furniture products in the future.”

VIKTORIA LAGUYO & DANIEL UBAS, KRETE MANILA

While concrete is more commonly used as a building material, in the hands of Filipino duo Viktoria Laguyo and Daniel Ubas, they see it as “a canvas for creativity”. They attribute it to how material exploration is deeply rooted in the daily life of their home country, “We look at the resources and waste streams around us – like coffee, capiz shells, concrete – and ask how they might be reimagined into something meaningful.”

At EMERGE, they presented the Mono Vessels series, crafted from concrete and biochar made with used coffee grounds from cafes in Metro Manila. The outcome is cylindrical vessels with striated surfaces that echo brutalist formworks and Roman columns. Look more closely and unmistakeable are flecks from the coffee grains streaking across them, bearing the same traits as concrete buildings that weather beautifully over time.

The collection is their solution to minimising coffee waste, which, when left to decompose in landfills, release harmful methane gas into the atmosphere. “We wanted to create a small cycle of sustainability, where we turn a daily ritual into vessels that hint at the future of concrete home décor and surface design,” they said.

Indeed, the pair are excited to take this material exploration further. Next up is the possibility of other forms of agricultural waste, opening up opportunities to work with local communities, engineers and fellow designers.

EWAN LAMM, ULTRAMAR STUDIO

Ewan Lamm of Ultramar Studio professes to a wide range of interests. From cultural heritage to contemporary design, identity exploration, myths and folklore, these are just some of the influences that dictate the work that he does. The reason? He comes from a mixed heritage of Hong Kong and British origins, while currently based in Spain.

“My interest in cultural narratives comes from my own experience of living between cultures and constantly navigating that space. Through my designs, I hope to evoke curiosity and encourage a deeper appreciation for cultural connections,” he explained.

His Citadel collection certainly ticks all these boxes. Inspired by East Asian palatial architecture and celestial mythology, it comprises a table lamp, floor lamp, and two illuminated sculptures. When lit, a soft, yellow light emanates, enshrouding the tiered geometries, distilled through a brutalist lens, in a cosy cloak.

This duality of East and West is a typical theme Lamm enjoys exploring. In Citadel’s case, he said: “It considers design as a tool for connection – one that questions how the past shapes the present, and how regional narratives can enrich global conversations without being diluted or exoticised.”

Ultimately, his goal is to merge cultural heritage with contemporary design, infusing new life into traditions, while demonstrating how Asian cultures are more than just a single, monolithic idea.